“An alternate way of viewing the world”: Suman Gopinath on Nasreen Mohamedi

Curator Suman Gopinath tells us about her admiration for mysterious Indian abstract artist Nasreen Mohamedi…

Karachi-born Nasreen Mohamedi (1937-1990) was an artist virtually alone amongst her peers, moving away from a conventional figurative style in the ’60s and dedicating her practice instead to exploring small scale, abstract geometric drawings.

Tate Liverpool’s new Mohamedi exhibition is the largest solo show of her work in the UK to date. Spanning semi-abstract, calligraphy-inspired inky paintings, to found photography used as the basis for compositions, to the exploration of grids and graphs, to astonishingly detailed ‘floating forms’, the exhibition mirrors Piet Mondrian’s journey — who has a co-current retrospective on the same gallery floor – from figurative to abstraction.

We sat down with Suman Gopinath (an independent curator who currently works with Tasveer Foundation, and India Foundation for the Arts, Bangalore, India) who has co-curated the Nasreen Mohamedi exhibition at the Tate Liverpool.

The Double Negative: Nasreen Mohamedi is still relatively unknown in the UK. How and when did you discover her work?

Suman Gopinath: I came across Nasreen’s drawings in the 1990s, in a book, Nasreen in Retrospect, which her family published after her death. This was the first time I set eyes on her beautiful line drawings. I actually got a chance to work with her drawings in 2000 when I curated the exhibition Drawing Space: Contemporary Indian Drawing with Grant Watson. The exhibition explored the idea of ‘drawing’ through the works of three artists — Nasreen Mohamedi, Sheela Gowda and N S Harsha. It was quite an adventure putting together a body of Nasreen’s work for this exhibition, as we had to literally begin with locating and finding her works all around the country, and then negotiating with the collectors to lend her drawings for the exhibition. This was because her work had not really been shown after she died in 1990.

I had the chance to work with Nasreen’s drawings again when I co- curated the exhibition Nasreen Mohamedi: Notes/Reflections on Indian Modernism, this was the first solo exhibition of Nasreen’s in Europe,it was initiated by OCA (Office for Contemporary Art Norway) and travelled to six venues in Europe and the Milton Keynes Gallery in the UK.

What did you think when you first saw these incredibly detailed, intricate, architectural drawings?

They took me by surprise as I had never seen any other work like this before. I used to work in a gallery then, and was used to seeing varieties of figurative work both on canvas and paper. So when I suddenly came across these delicate, detailed drawings I made up my mind that I had to work with them some day!

Have you always been interested in drawing? Or have you found a new love of drawing through Mohamedi?

I have always been very interested in drawing. When Grant and I started working on Drawing Space, we tried to look at the use of the ‘line’ in drawing, painting and installation works by contemporary artists in India. We also tried to think of the ‘line’ as a device for negotiating space, by weaving a thread between the more empowered use of the line by contemporary artists from India today and the Company School painters whose ‘line’ was defined by their colonial patrons.The exhibition had a very large body of drawings by Nasreen, wall drawings and paintings by N S Harsha (whose work was a response to the Company School paintings of the 19th century) and an installation by Sheela Gowda. Alongside the works of these three artists ,we had a selection of slides of Company School paintings from the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum. So yes, I have always been interested in drawing.

Mohamedi studied art at Central St Martins (1954-57); what impact do you think this period had on her work? Who was she influenced by?

Nasreen was very young when she went to study in the UK. She had barely finished her schooling in Bombay, after which she went directly to study at Central St Martins. Her formative years as an artist were spent in the UK – so I’m sure her education there and the works of other artists she might have come across during her time in London affected her practice as an artist.

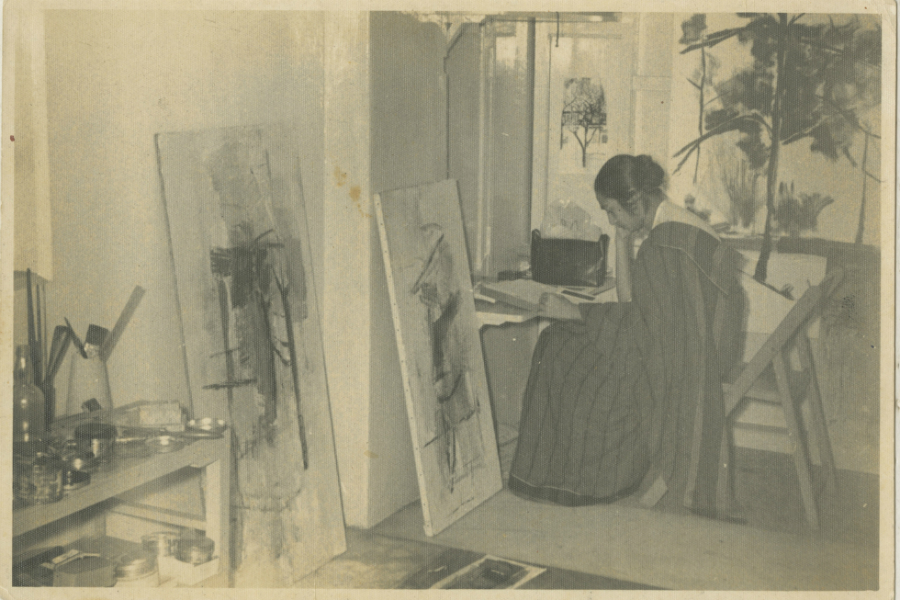

Art historian and friend of Nasreen, Geeta Kapur, sees influences of the French postwar abstractionists, Georges Mathieu and others on Nasreen’s early abstract phase, where nature is still the ‘remote referent’. After Nasreen came back to India she shared her studio at the Bhulabhai Desai Institute in Bombay with other significant abstract artists in India, most notably V S Gaitonde, whose large monochromatic canvases and calligraphic qualities had an impact on her own work.

Kapur sees connections between Nasreen’s mature ink and graphite drawings from the ’70s with early Mondrian. Interestingly, Michael White (curator of Mondrian & his Studios)was just telling me that there was a very large exhibition of Mondrian’s work at the Whitechapel in 1955 and Nasreen might well have seen that!

As regards influences, Nasreen’s friends and colleagues say that she admired other artists Klee & Kandinsky, to name a few, but was not influenced by any one artist in particular.

There is, of course, a visible leap from figurative to abstraction in Mohamedi’s paintings and drawings as you walk through the exhibition, just as in the Piet Mondrian show; nature morphs into architecture. Do you think that we’ll ever really know the catalyst for this, given the lack of information to survive Nasreen? Or do you just think it was a natural progression, given all the different places that she lived (London, Paris, Bahrain, Mumbai, Baroda) and the people she met?

If you look closely at the earliest work we have in the exhibition, the landscape with houses, trees and a fence, you can see intimations of what was to follow — the landscape is made up of a series of vertical and horizontal lines. So I think that perhaps you could see a kind of progression, where she moves from figurative works based on landscapes from nature, and then on, where the image is abstracted from nature, and then there follows a series of subtractions, and what we are left with are the series of lines upon lines.

You and co-curator Eleanor Clayton have had to estimate the chronological order of the works in the exhibition, as Mohamedi never signed or dated her work. Why?

It is true that Nasreen never signed or dated her work. I think we have about three or four signed works in this entire exhibition!

As there isn’t much documentation or a catalogue raisonne of her work, we have had to rely on friends and colleagues of Nasreen who have given us an idea of when certain bodies of her work were made, and based on that, we have been able build a chronology of her practice. Eleanor and I have placed her work in a kind of chronology to guide the viewer through Nasreen’s path to abstraction.

Tell us about her studio.

There are many myths about Nasreen’s studio in Baroda, which people say was like an extension of her practice as an artist. Unfortunately, I never got a chance to see it because it was sold after she died. But her studio has been described as a ‘Sufi’s den’, a ‘pure space’ — a retreat away from the bustling city outside. It was sparsely furnished, and her work table, an architect’s table , occupied pride of place.

The studio was said to have had a grey floor which Nasreen ritualistically cleaned every morning before she started work. Nasreen would sit cross-legged on the floor for hours, in front of her tilted drawing board with her drawing tools beside her, making her black and white drawings. According to friends, Nasreen had an amazing vanity about the tools she used… her whole process of working, friends say, was like a ritual, right from the time she cut her paper, either square or rectangular sheets of paper, till the time she completed her drawings. Music was an essential element of the time that she spent in her studio and friends remember her love for Hindustani classical music.

As with Mondrian, did she have many friends and peers visiting her studio?

I think that there is a degree of similarity between Mondrian and Mohamedi apropos of what their studio meant to them. For both, it was in a way an extension of their practice as an artist, and in some sense was reflected in the kind of work they made. For both, the studio seemed to be an austere space, almost a sacred space , but I think the similarity ends there.

From the photographs of his studio, which are iconic in themselves today, it appears that this was the space that Mondrian used to experiment in — he covered the walls with works and worked on the walls themselves — and invited people to see them. To him, the studio was both an intimate and a social space. But I’m not sure if the studio worked in the same way for Nasreen.

From what I have heard, she never hanged her drawings on the walls of her studio, the drawings were in fact stacked away in separate piles in her drawer, and this was how they were found when she died. Though Nasreen was very connected with people – her fellow artists, friends, family, students — her studio was more a sanctuary for reflection, I think, a place she retreated to when she wanted to work, this is how it seems to me, from the stories I have heard.

I understand that her students at the Maharaja Sayajirao University loved her?

Yes, Nasreen was a very unusual and exceptional teacher I think, from what her students and colleagues tell me. Her close friend and fellow artist Nilima Sheikh (who also taught in Baroda at the same time as Nasreen), remembers that Nasreen was hesitant about teaching in the beginning, but slipped into her role as a teacher very easily. Nasreen taught the students on the Foundation course at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Baroda from 1972-1990 when she died.

Her being there, in Baroda, at that particular moment in time was very significant, because the painting department in the 1970s was known for its figurative narrative style of painting. Nasreen , through her own practice as both artist and teacher , tried to do away with the idea of the ‘masterly drawing’ and concentrated instead on pristine forms, ‘edge to edge’ drawings with great attention to both spatial relationships and surface. I think this in fact offered her students an alternate way of viewing the world and the idea of drawing.

Female artist role models can be few and far between. Did she also have the respect of her male peers?

Yes, Nasreen was very well regarded both by her female and male peers. Hers was a singular practice, and for all her modesty and the struggles she went through as an artist, Nasreen was said to have had an amazing confidence in what she was doing.

Where do you think her confidence came from? As a female artist, in that culture, at that time?

It probably came from a commitment, a belief in herself , and what she was doing…

Laura Robertson

See Nasreen Mohamedi at Tate Liverpool, 6 June – 5 October 2014 — tickets £10/7.50, including admission into Mondrian and his Studios: Abstraction into the World

Read Suman Gopinath and Grant Watson’s essay on ‘The Linking Road’, from Drawing Space: Contemporary Indian Drawings, 2000

Main image: Nasreen at her studio in Bombay at the Bhulabhai Desai Institute, dated 2 Nov 1960. Courtsey: Sikander and Hydari Collection