A Special Kind Of Devil: Remembering H.R. Giger

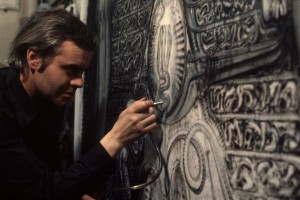

H.R.Giger died last week aged 74. Here, C James Fagan describes how a man gripped by night terrors became a visionary artist and inspiration to many…

For many creative types, there are points during your lifetime where you begin to seriously consider the possibility that you can actually make a life out of drawings and other creative activities. For me, and others of my generation, there are names whose work created an imaginative lightning rod, bringing to life many artistic ambitions.

By no means a comprehensive list, it includes the likes of illustrators and concept artists Ralph McQurrie, Syd Mead, Moebius and H.R. Giger. The tragic thing about this list that only Mead survives; the most recent loss being the Swiss surrealist Hans Rudolf Giger.

Giger’s recent death has made me reflect on his influence. Though he had been an artist for many years, there’s no denying that what shot Giger to international fame was the birth of cinema’s worse nightmare: the titular, acid-dripping, carnivorous creature from Alien. I was probably a teenager when I actually saw the film, though I have earlier memories of feeling uneasy while looking at promotional posters; glowing, steaming eggs amongst strange landscapes that seemed to incorporate human bodies.

Being a fan of science-fiction and growing up in a pre-digital world, I fed my interest in the genre through regular library trips, selecting books with titles like The Best Sci-Fi Films Ever!, or The Bumper Book of Aliens and Monsters. There were a number of these books, and nearly all of them featured Giger creations – The Space Jockey, The Derelict and The Alien. These images where in equal parts attractive and disturbing, and the text around them used provocative phrases like ‘bio-mechanical’.

These pictures and the reprints of Dark Horse Comics was enough to spark something in my imagination. So when I discovered a copy of HR Giger Arh+ in a discount book store, I quickly snatched it up. Therefore making it the first artist book I ever bought, and making Giger the first artist I conducted independent research about.

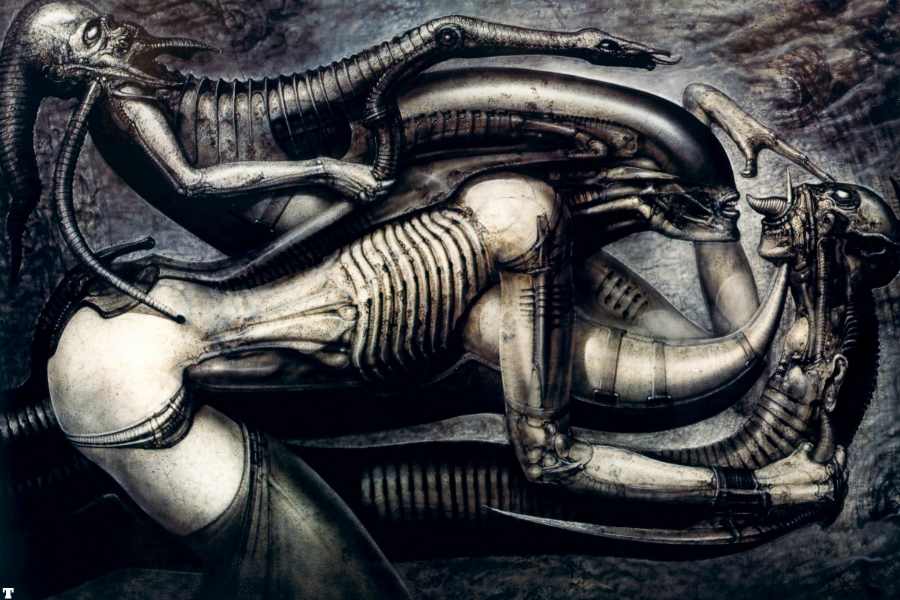

Around this time I had begun the long journey of higher and further education, though I didn’t buy the book for solely artistic reasons. I bought it to learn more about his most famous monsters and where they spawned from. In the pages of the book, I discovered Giger’s World One; largely monochrome, where strange humanoids have intercourse with and become the bio-mechanical landscapes they inhabit. It’s a world where something innocuous — like the back of a bin van — can morph into vaginas, as in his Passages series.

It’s a nightmarish world of Freudian worries, and it’s no surprise that Giger suffered from night terrors, which he noted down in a dream diary. It was probably this dark work of sexual nightmares that first attracted the filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky, who asked Giger to create the world of the evil Harokken in his abortive version of Dune. When scriptwriter Dan O’Bannon presented Necronom IV to Ridley Scott (Giger’s surrealist print that formed the basis for the Alien design), they knew they had a special kind of devil; one which would “Fuck you as well as kill you”.

Within Giger’s work we recognise something we don’t really want to see. In many of his paintings, there is a sense of discomfort about our own roles in the business of reproduction. Like many surrealists before him, Giger swam in the murky waters where our darkest desires lapped against the shores of our normal lives.

In retrospect, I wonder if this element is what made Giger so appealing to my adolescent self. Forgive the amateur psychiatry, but I have to consider that within the squirming, interlocking organic machinery of Giger, I saw a reflection of my changing body. Within that, perhaps I and many others found a strange of comfort, or at least a possible way of trying to understand the strange role that puberty has set out for you in the adult world, and all the squishy, fleshly promise it holds.

Beside this rather disturbing element, Giger also provided a gateway to the wider world of art for a kid who didn’t really visit art galleries; this meant learning names like Max Ernst and Francis Bacon. Bacon’s Three Studies for Figures at the Base of the Crucifixion provided inspiration for the infamous Chestbuster.

Though Giger will be remembered as the guy who created Alien, this is not doing him a disservice. It marks him as the catalyst for many artistic and creative careers across many mediums. Therefore making Giger, in my eyes, one of the most influential artists of his generation.

C James Fagan

See more of H.R.Giger’s work here