Sociopaths, Sunshine and Shadow: The New Film Noir

As Bastards (Les Salauds) enjoys a nationwide release, Toby Hood investigates the evolution of film noir, and the dangers of veering into pastiche…

From its beginnings in German expressionism, film noir flourished during the ’40s and ’50s, when the backdrop of global conflict, espionage and conspiracy lent itself to the twists and turns of the style. Since then, the genre has become synonymous with the period, and contemporary noir, or neo-noir, is commonly seen as a throwback to that epoch.

“Like surrealism,” notes critic Philip French, “once a challenging, subversive style, noir has become just another element on the fashionable filmmakers palette.” I disagree. His disdaining words do little justice to the survival and good use of those elements from that seminal noir-period in films today. While it is true that film noir isn’t still evident in its purest form, flavours of that bygone age have been kept alive in cinema over the last 50 years, perennially lingering on ‘fashionable palettes’.

Throughout the latter half of the last century, noir had readily been conflated with the crime-thriller genre, most notably in the films of Kevin Spacey — The Usual Suspects (1995), Se7en (1995), L.A. Confidential (1997) — and Quentin Tarantino — Reservoir Dogs (1992), Pulp Fiction (1994), Jackie Brown(1997). The Coen brothers claim the most influential contribution in contemporary film noir, most adroitly in thrillers like Fargo (1996) and, more recently, No Country For Old Men (2007), where high body counts and minimalistic scripting provide an affecting level of tension.

The sun-bleached, desert-based settings of pictures like No Country, and the abandonment of trilby-hatted private eyes in favour of denim-jacketed sociopaths, has led critics to consider the evolution of film soleil as a suitable taxonomy of current noir trends. ‘Putting the lights on’ in a noirish setting, film soleil puts in plain sight what noir leaves in shadow; like many of antagonist Anton Chigurh’s brutal murders in No Country, shootings are carried out in broad daylight with little fuss and much clarity.

Recent years have seen the birth of another sub-genre in Nordic-noir, nurtured by exported television shows from Scandinavia and leaking on to the silver screen, in adaptations of Stieg Larsson’s The Girl Who series. This, in turn, has fed the increase in more European crime novels, marking a tribute to the French literary tradition of série noire. Other than its relationship with pop lit, Nordic noir is so called because it places the investigator back into the centre of the plot; it is the unravelling and study of the crime that retains audience attention.

When we watch The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo (2011), waiting to uncover the criminal reinvigorates the base interest that noir originals like The Third Man (1949) capitalised on to attract audiences decades before. The bleak setting of a near-deserted village on the coast of a wintry Sweden bares a hopelessness and despair befitting the noir style; while the sex sequences and unscrupulous crimes of the principal characters throw in the themes of infidelity and moral ambiguity for good measure.

Film noir may not have survived in any immediately recognisable sense, but this only shows the problems with distinguishing any genre, particularly one associated so closely with a particular group and distinct period of time. To quote another critic, if only for balance: “Defining noir is a task more like classifying architecture. A bungalow is still a house but it is not like a thatched roof Tudor house; we see the differences that link the two houses to their individual categories, yet grasp their broad similarities to the larger base set to which they all belong.” Douglas Holm’s architecture analogy shows how noir has provided solid foundations for murder mystery, structured the gripping tension of psychological thrillers and furnished the likes of hybrid movies with shady characters in dark environments.

In a recent conversation with a university lecturer, who specialises in the subject, it was put to me that “it would be difficult to make a film that avoided any parody or pastiche of traditional noir.” Tom Konkle and Brittney Powell’s independent production Trouble Is My Business confirms that idea.

Having financed their project from crowdfunding website Kickstarter, the duo produced their version of a 1947 investigation plot with all the ingredients of a noir classic. Having only seen the online trailer myself, it would be unfair of me to pass any conclusive judgement; but the trailer gives the sense of a film that aspires to be something bigger than itself, yet has fallen entirely into pastiche, missing the subtlety of its predecessors. Watch the trailer here and decide for yourself how successfully the crew have paid homage and avoided my own critical class of nada-noir.

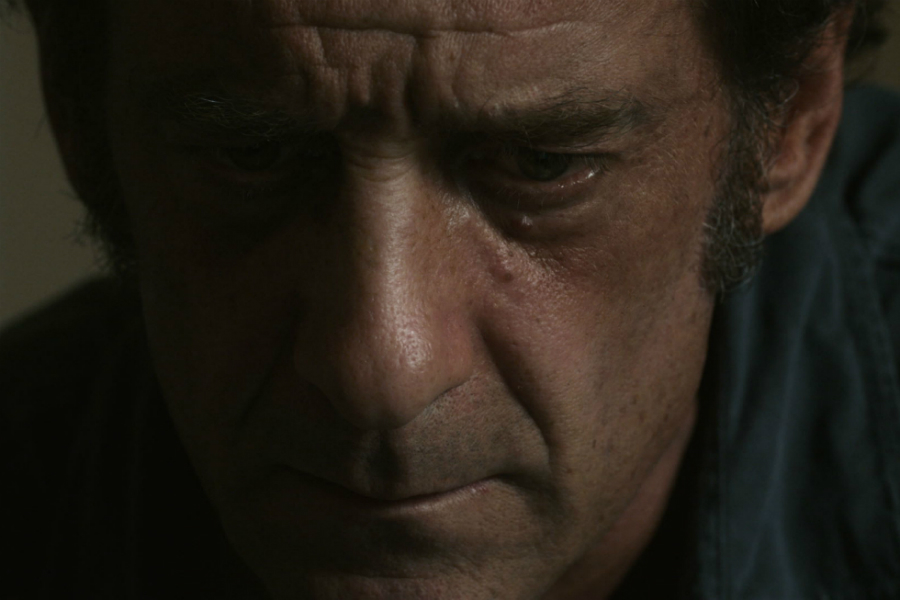

There is more solid hope, however, in legendary French director Claire Denis’ harrowing Bastards (Les Salauds) (2012), on limited release throughout the UK this week. Described by the Guardian’s Peter Bradshaw as “menacing”, “atmospheric” and “headspinning”, Denis sacrifices plausibility — using a fragmented, non-linear structure — in order to achieve a “macabre and dreamlike” quality that is every bit the noir custom.

And so we come full circle in refuting Philip French’s claim of the sorry state of contemporary noir as a reduction of its previous glory; cinema where everything else gave way to expression and aesthetic. Using noir as a mere fashionable element seems a worthy compliment to a genre that has always been about style.

Toby Hood

Bastards (Les Salauds) is on limited release across the UK this week, including at Cornerhouse Manchester from Friday 28 February (5.50pm), and a one-off screening at FACT Liverpool Tuesday 18 March (6pm)