Keywords, Raymond Williams and The Evolution of Language

What does ‘culture’ mean? And can art help us understand? Laura Robertson on a new exhibition exploring the ‘key’ words of the English language…

“The fact is, they just don’t speak the same language.” So said a young Raymond Williams in 1945, just released from the army and now back, at home, in Cambridge University. Now a war veteran, he had lost touch with all his friends over that four and a half year period; bumping into an old army acquaintance, they marvelled at how strange the world had become in their absence.

Both thinking that four or five years really hadn’t been that much time at all for things to change, Williams became preoccupied with the differences around him, and particularly the way people talked. There had been, in his eyes, a shift of meaning within the English language; the values, feelings or ideas attached to words had subtlety changed.

One such word was Culture; the young academic noticed that the people around him were using it more frequently and with a different meaning: “I had heard it previously in two senses: one at the fringes, in teashops and places like that, where it seemed the preferred word for a kind of social superiority… yet also, secondly, among my own friends, where it was an active word for writing poems and novels, making films and paintings, working in theatre.”

He had identified a pivotal thought process that would make his career. Firstly, that Culture was a “difficult word, a word I could think of as an example of the change we were trying to understand”; and secondly, the importance of analysing the historical, anthropological and social changes that were sculpting our language in such an accelerated and complex way it was almost that we didn’t notice. “In a large and active university,” he noticed, “and in a period of change as important as a war, the process can seem unusually rapid and conscious.”

Fast-forward 31 years and Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society was published; Williams had dedicated his career to understanding our use of ‘key’ words, their origins and the range of meanings attached. Look up Culture in the 2014 edition (the format is similar to a dictionary) and you will learn that its original meaning comes from other words like Inhabit, Cultivate, Honour, Civilisation, or Intellectual; there are lots of variations, including its derogative use in terms of class distinction.

It “has been connected with uses involving claims to superior knowledge (cf. The noun INTELLECTUAL), refinement (culchah), and distinctions between ‘high’ art (culture) and popular art and entertainment”; recording “a very difficult and confused phase of social and cultural development.”

We are pointed in the direction of connected words, in order to gain a broader understanding — Aesthetic, Anthopology, Art, Civilisation, Development, Folk, Humanity, Science and Western — revealing, somewhat, the extent of interconnectedness between language, history and behaviour.

There’s something really satisfying about browsing the pages, picking out words at random. Look up Sex and amuse yourself with references of Sexlessness (19th century) as ‘a kind of impotence’; Sex-abolitionists, or those who were opposed to the sexual discrimination against women; Sexualogy, or the science of sexual relations; and moving into gender politics with Sexism and Sexist (which only came into general use through the 1960s), and Sex-objects. Philosophy, on the other hand, “has retained its earliest and most general meaning, from fw philosophia… the love of wisdom, understood as the study and knowledge of things and their causes.”

This Friday, Tate Liverpool presents Keywords: Art, Culture and Society in 1980s Britain, a major exhibition and lecture programme, in partnership with Iniva, that expands upon Williams’ studies of words through painting, sculpture, photography and video from the Tate Collection. The words featured — Structural, Private, Folk, Violence, Criticism, Liberation, Formalist, Myth, Anthropology, Native, Materialism, Unconscious, Theory — are explored by provocative works from 60 artists, including Sunil Gupta (London Gay Switchboard 1980), Derek Jarman (Ataxia – Aids is Fun 1993), Sir Eduardo Paolozzi (Kardinal Syn 1984), and Peter Kennard (Haywain with Cruise Missiles 1980, main picture).

This is British art made through a period marred by political strife, which in turn (of course) had a direct impact on culture; from miners strikes, race riots, protests against nuclear power, gay liberation and feminism, to the opposition of British rule in Northern Ireland. This period of intense social change in some way mirrors Williams’ own experiences of the late 40s, as well as our own modern experiences of global austerity, protest and war; one of “unusually rapid and conscious” transition.

With a specially designed exhibition space by artist Luca Frei and designer Will Holder (the stars of the show here are Williams’ words, lovingly recreated in huge, handwritten typography), it’ll be interesting to see how the artworks are challenged by keywords, and vice-versa. Let’s hope for a deeper understanding and dialogue of the language we share, in the spirit of one of our most important thinkers.

Laura Robertson, Editor

Keywords: Art, Culture and Society in 1980s Britain opens at Tate Liverpool Friday 28 February-11 May 2014, £8/£6 entry fee. See site for a full list of talks, workshops and tours

Open daily 10am-6pm

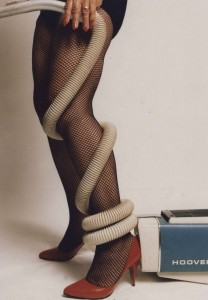

Main image: © Peter Kennard (image courtesy Tate). Centre: Jo Spence, Libido Uprising Part I, 1989 © Estate of Jo Spence, Courtesy Richard Saltoun Gallery, London