Out of Ice: Elizabeth Ogilvie

Oli Rahman speaks to an artist intrigued by glacial landscapes, our relationship with water, and the impending “apocalyptic ice melt”…

Over the past decade Scottish artist Elizabeth Ogilvie has been exploring the theme of water through her work.

Inspired by her recent trips to Greenland, Ogilvie’s most recent exhibition, Out of Ice, documents the beauty of an ever-changing glacial landscape, as well as providing insight into the lives of the indigenous Inuit people.

It’s made-up partly from fieldwork, video footage, and watery installations, and is set in Ambika 3, an unconventional exhibition space beneath the University of Westminster (near Baker Street) in North West London.

While I wander through the show before interviewing Ogilvie, I find myself away from the main exhibition space in a separate room. A screen is playing shaky footage of a howling Antarctic gale. A team of scientists go about their work — using machines to excavate four kilometres of ice as part of the Lake Ellsworth drill site, Western Antarctica — to collect frozen sediment that might tell us more about, well, everything and anything.

It looks exhausting, even with all the heavy duty kit, as they have to sterilise everything before use to prevent contamination of the samples. And the noise of the gale is deafening as it clatters through the hall.

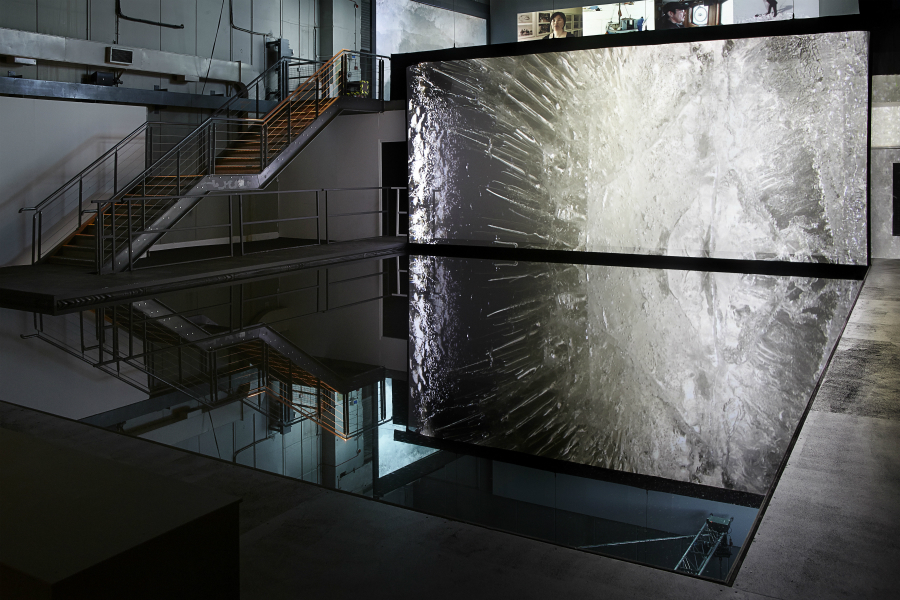

The other main room in the subterranean space of Ambika 3 is more aquatic and peaceful. There are four screens playing video footage, and two sunken pools of water, about knee depth with some cracks and fractures running along the base.

The clips are of ice crystal flows and ice formation (gorgeous to watch), filmed in 2013 around Oqaatstut, Northern Greenland. Another shows an Inuit talking about the ways in which melting ice sheets are impacting upon their culture; another follows Inuit fisherman and explorers.

There’s also footage of vessels navigating the occasionally perilous ice sheets, where the risk of being marooned or even sunk are ever present.

The sound of trickling water is captivating, and with the muted lighting, the space feels almost like an indoor Zen garden.

One pool in Ambika 3 is bordered by a two layered projection, two changing images of ice with a corridor running through. Viewers can walk between the two images as if it were an ice tunnel; from a distance it looks 3D, like a hologram of a real glacial fissure.

Ice is beautiful at a microscopic level.

The artist behind it all, Ogilvie, sits by the pools. She’s silver haired and softly spoken, with a Scottish lilt that reminds me of my relatives from the Highlands and Islands.

She seems very taken with Greenland — she first went there five years ago and has returned various times since, taking along a stripped back film crew last year. I sit down with her to find out more about the exhibition and her ideas.

Where did the idea for Out of Ice come from?

I tend to be led by my work and I’ve been working with the theme of water in various forms for the past decade or longer. The work led me on to investigate ice and then I did a lot of research, a lot of reading.

How did you end up visiting Greenland?

After I became very fascinated with the subject of ice, I thought, ‘I have to go somewhere to actually see ice in the environment in a way that’s different to our own climate here.’

I did a bit of research and ended up in Oqaatstut, which is beside the biggest glacier in the northern hemisphere. That whole site has become a World Heritage site and it’s remarkable in terms of the amount of ice floating by it, filling up the sea, giant icebergs… I went out there to research ice and learn more about it.

The temperature there’s cold but I find it a welcoming environment.

Is there an environmental message underlying the research?

I’m not spelling it out but I’m saying it in my own way. Ice melting into a pool has a beauty to it but it’s also quite contemplative, but there’s also a story, there’s also a message then with these melting ice forms here as well. I’m emphasising that fact. There’s one film here that’s of ice crystals forming.

I suppose I’m asking myself if this process of melting can be reversed the future. I have an inbuilt compass which points me north anyway, and I’m always fascinated by the environment in its various forms.

What made you interested in the Inuit?

By direct observation, I became really interested in the inhabitants there, which hadn’t entered my work before. Adding in the human perspective is very important. And I realised these people were quite remarkable living in these extreme conditions and in being able to navigate their way through it and through reading the natural world, reading nature and reading ice.

What surprised you about the Inuit’s relationship with ice?

They don’t have a God. The natural world is part of them, they regard it as their revered partner. There’s no Inuit word for environment. It’s part of them, as is the ice.

I’ve learned over the years how their understanding of ice helps them navigate it and helps them understand climate change, hunting, sledging, pastime. They know whether it’s safe to go close to an iceberg, whether it’s about to flip.

They see ice as their garden to enjoy in the winter. It becomes extended territory, there’s a whole language based on it. It’s quite a social event, to be able to get back onto the ice every year. They go sledging on it, dog sledging, hunting, and they get a lot of their food supplies and animals skins that way.

Could you explain a bit about the Lake Ellsworth video?

That is to do with the research going on there. They are boring into four kilometres of ice so that below they’ll find sediments containing forms of life that we don’t know about yet.

It’ll contain a lot of information about past climates and hopefully future climates too. There was a lot in the press about it failing this last year. They need longer. They’ll be going back next winter to get the samples they didn’t manage to.

There were various logistical things that didn’t go right — engines that didn’t work, e.t.c., but they weren’t really failures, more logistical issues. I’m working with them and will be in the future.

Do you consider yourself a scientifically minded person?

Not necessarily; as I say the work is leading me to read and understand work by scientists. I have done a lot of reading and I find it fascinating.

What do you want audiences to take away from the exhibition?

I wanted to get a sense of the ice walls, of the timelessness of the ice strata that gives you millions of years of information, a bit like a rock strata.

We’ve had a lot of extreme weather linked with ice melt, and this is to do with money at the end of the day. Greed and industries which cause it. We all know that and scientists warn us.

In one of the films I speak about traveling through the icebergs and halfway through it I’m talking about the apocalyptic ice melt. That’s about all my presence in it, I tend to remove myself from the show. But I still want them to find it as extraordinary, exhilarating and fascinating as I do.

Oli Rahman

Out of Ice, Ambika 3, University of Westminster — open until 9 February 2014 (free entry) — will move to Osaka, Japan in the future

More on the exhibition themes here

Main image courtesy Julian Abrams