Art Turning Left — Reviewed

Revolutionary thought and ideas inform a new exhibition and Tate Liverpool’s future, finds Laura Robertson…

How ‘left’ is Tate? Alongside the corporate sponsors and blockbuster artists, lies an organisation responsible for rejuvenating an ’80s Liverpool at its darkest hour, into a Capital of Culture and one which could host an international biennial. It’s tempting to consider the suitability of the venue for an exhibition exploring left-values (also noting the £8 entry charge), but that’s not really what this show is about.

The exhibition aims to examine how the production and reception of art has been influenced by left-wing values, rather than focusing too hard on the various political messages behind the works. It does so through an incredible array of well-known, emerging and outsider artists from across the globe, and realistically Tate is probably the only UK gallery to be able to pull an exhibition off on this scale.

But is it any good?

What strikes you first is the enormous showcase of international works selected from an extensive period, 1789-2013; secondly, the invisible curatorial hand that maintains a steady questioning and prodding of the audience throughout. This is an exhibition eager to encourage the audience’s own analysis of the works on display.

Each room is framed by a different question, deriving from three main values that the ‘left’ might represent: equality and rights, the collective or the supremacy of the group, and alternative economies for the future. ‘Can art infiltrate everyday life?’, ‘Do we need to know who makes art?’, ‘Are there ways of distributing art differently?’; each question makes you interpret what you’re looking at, and why it’s there. In this the exhibition is successful; the guiding hand steers away from being patronising.

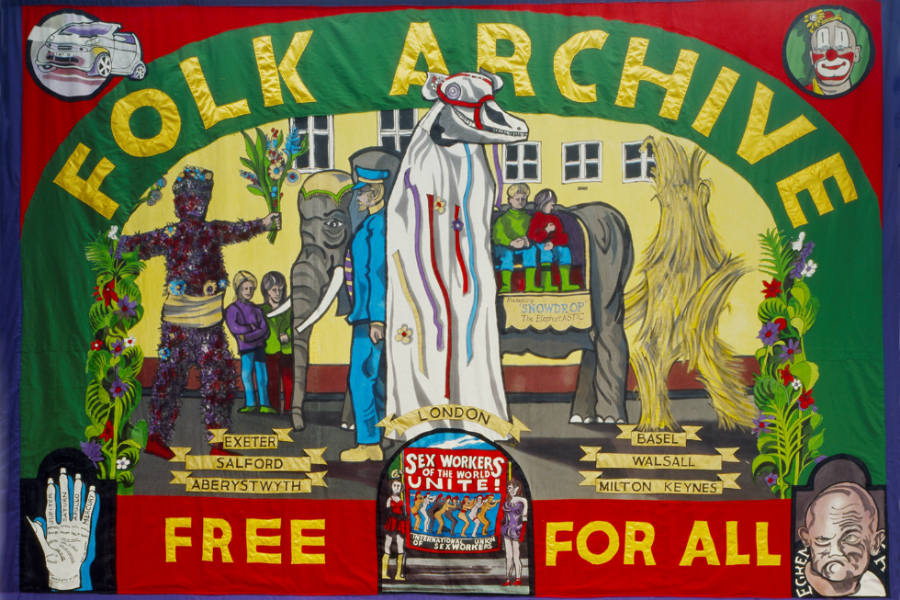

So what artworks do the rooms present? In ‘Does participation deliver equality?’, artists are inspired by action. Here resides Jeremy Deller’s Folk Archive (2000-2006); photographs of the odd things collected and put on show by the general British public, often in domestic settings. Painted rockeries; a mural on the side of a building; nick-nacks, a home-made costume.

David Medalla’s A Stitch in Time (1968-1972), which he calls “participation-production-propulsion”, asks the audience to sew small objects of significance onto a large blank cloth in a public space, encouraging concentration and, it became apparent, the transformation of a viewer into performance artist. Set in a prominent position in the room, no one was brave enough to jump from observer to participant while we were there.

If you were hoping for quiet contemplation, Julio Le Parc’s Ensemble de onze jeux surprise (1967) puts paid to that idea. A wall-mounted sculpture of motors, strips of metal, fans and sticks could all be set off into an orchestra of clanging if you chose to press a series of buttons, frightening the wits out of other visitors.

Much fun was also to be had with Ruth Ewan’s A Jukebox of People Trying to Change the World (ongoing since 2003); an operating CD jukebox of protest and political songs. Listening to our choice, Stereolab, in this context did feel like a giddy mini-rebellion; gallery etiquette be damned!

In another space, the question is posed: ‘How can art speak with a collective voice?’ Maximilien Luce’s oil on canvas L’aciérie (1895), uses the pointillist technique in a literal interpretation of Anarchist-Communism; individual dots of paint combine to make one collective image.

The Mass Observation Movement (1937) is widely represented in this room; a team of ‘observers’ and volunteer writers, brought together to study the everyday lives of ordinary people in Britain. Some observations are printed on the wall: ”Behaviour of people at war memorials; Shouts and gestures of motorists… Anthropology of football pools; Bathroom behaviour”…

Alongside, Martha Rosler’s social activism project, If You Lived Here (1989), sprawls across walls, tables and display cases. An exhaustive collection of notes and plans, posters, announcements, press releases, photographs, research and newspaper clippings on homelessness, it is a collaborative collection created with the artist, homeless group Homeward Bound, advocacy and activist groups, architects and urbanists from Soho, New York.

An so on the exhibition goes; this is just a slice of what to expect. Art Turning Left is a show of ideas, rather than one of shock-value; a subtle display on a grand scale of what artists can and have achieved when inspired by equality and the collective voice.

Despite being enormous, the exhibition is tightly managed, which is a good thing, giving order and a sense of changing politics and artistic trends. The many questions are very open to interpretation, encompassing so many different styles and production values. This left us, three hours later, completely exhausted and feeling that we’d only scratched the surface.

A further visit feels essential. The narrative weaves in and out, making connections, throwing out new ideas and bustling you into a whole new section, and therefore question, at every turn.

There’s an additional thread to this show that is worth mentioning to those interested in curation and interpretation. Art Turning Left is first exhibition to be curated by new artistic director Francesco Manacorda (alongside assistant curator Eleanor Clayton and LJMU researcher Lynn Wray), meaning that this work was always going to be seen as a debut performance and a marker for things to come.

Present at the opening last week, we heard Manacorda’s vision for the exhibition and indeed for Tate Liverpool, explaining a drive towards what he calls a ‘magazine principle’: as a medium-sized gallery, different exhibition sections should, in his eyes, be relating to different parts of the Tate building, connecting the whole creative programme and organisation’s ambitions, whilst making the art more accessible and the experience more valuable to the visitor.

The magazine principle, as we saw it, manifests itself through the usual free user guides and on-hand gallery assistance, as well as a new magazine (covering the programme as a whole), and the wall-mounted questions or prompts as seen in this show.

Art Turning Left is the pilot for these ideas and as such, a showcase for both Tate Liverpool’s reach and Manacorda’s ideas for the future of the organisation.

Laura Robertson, Editor

Main image: Jeremy Deller and Alan Kane, The Folk Archive 2005, Banner by Ed Hall ©The Artists, Courtesy the British Council Collection

Art Turning Left continues at Tate Liverpool until 2 February 2014