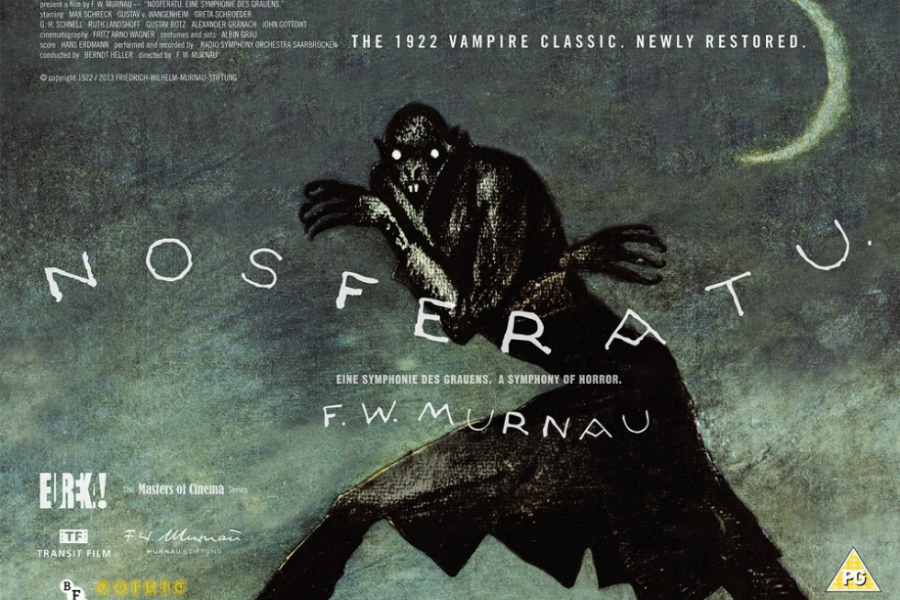

Nosferatu and the Early Achievements of Horror Cinema

Adam Scovell salutes a classic of the horror genre and the films that laid the groundwork for its success…

In his excellent 2010 series, A History of Horror, Mark Gatiss stated that the cinema was made for horror films; arguing that no other type of film makes such use of the medium or environment of cinema so well as this particular genre.

Looking back into the first decades of film, it is clear that the era’s directors also saw the potential and power beneath the surface, and one film has come to represent this magnificantly. F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (1922) is not by any stretch the German director’s best film, but Nosferatu still seems to edge ahead – at least in terms of public consciousness – with its imagery creeping into all avenues of popular culture.

Nosferatu is by no means the first of its kind. It seems almost mundane to point out the film’s ties with German Expressionist film, but this movement in itself seems to have solidified many of the ideas in early horror cinema. Before Nosferatu’s inception, we see a wealth of horror cinema engulf the big screen, almost as if the genre was already a mainstay of the medium (which it was in literature).

1920 saw Robert Weine’s The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (a film not entirely unlike Nosferatu stylistically) push a seismic change on both cinema and horror. Some argue that Caligari is the real starting point for horror, even ahead of Nosferatu, but Weine had been experimenting with the genre even years before.

His 1917 film Fear seems maverick-like in its early status as a horror film, making the director (who would go on to make other silent horror masterpieces such as The Hands of Orlac (1923)) a natural bedfellow to Murnau, whose constant experimentation with the genre still edges him ahead, however.

Along with the films of Weine, Murnau would have also been around films such as Paul Wegener’s The Golem (1920), Benjamin Christensen’s Haxan: Witchcraft Through The Ages (1922) and Victor Sjöström’s The Phantom Carriage (1921), amongst many others. This sort of atmosphere in film no doubt made it ripe for a roaring success such as Nosferatu to come along.

Murnau was already dabbling in horror at the same time as his peers. The now sadly lost version of his Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (Der Januskopf, 1920) is said to be one of the director’s early forays into the genre (casting horror legends Conrad Veidt and a young Bela Lugosi) while Murnau’s The Dark Road (1921) showed a very different type of vampire.

While Nosferatu may perhaps have been the first supernatural-infused vampire film, the term “vamp” meant something entirely different to the fanged presence of Max Schreck. In films such as The Dark Road, Louis Feuillade’s Les Vampires (1915) and Robert G. Vignola’s The Vampire (1913) “vamp” refers to a type of female character more in line with the femme-fetal of film noir. It is fitting then that Murnau would be responsible for using “vamp” in this way before being the person to change it to the more blood-sucking variants.

There’s even something vampire-like in Murnau’s The Haunted Castle (1921) with Count Oetsch inviting himself to the gathering at a rather creepy castle. It seems that Murnau and the filmmakers around him were building up to a Stoker adaptation (at least unofficially), as if he and his peers were preparing audiences through constant streams of quality horror until hitting them with a symphony of it in Nosferatu.

It’s easy to see why the film has made such an impact. Murnau has taken everything around him from gothic tendencies to Expressionism’s visuals and put it all into one picture.

Borrowing from Bram Stoker’s Dracula is so unbelievably obvious from the outset that it’s surprising Murnau thought he could get away without paying royalties to Stoker’s estate (Stoker’s widow famously sued Murnau, won and then had all the prints destroyed, at least all of the prints known about). Its tale of vampirism and a radiant evil travelling around Europe for the sake of an attractive woman happily survived; showing it to be pure gothica, reflected in the film’s visuals.

The imagery and make-up in particular is still chilling, using the most of shadows; while Schreck’s profile is perhaps the creepiest in cinema, with scenes of his shadow floating along a hallway and his outline being seen in a distant, abandoned warehouse standing out.

Murnau doesn’t seem too interested in the implications of vampirism or the deeper themes of Stoker’s novel. Instead he concentrates on the visual potential that such a source can provide, mixing it with his own talented eye for composition to create quite a simple but well told story of gothic obsession.

Murnau would continue with gothic exploration in (the arguably better) Faust (1926), but it is Nosferatu that has cemented his place in horror cinema. Even with the quality of film that was born around it, they seem more like excellent scout posts, checking the area is safe before letting the big guns come through.

Some of these scouts have full blooded histories and influence of their own, but it is Nosferatu that is remembered most readily and rightly so.

Adam Scovell

The new restoration of Nosferatu, released as part of Eureka Entertainment’s Masters of Cinema Series, is out now at selected cinemas across the UK

Read our article on Celebrating 90 Years of the Vampire in Film