In Profile: Jackson Pollock

Conal Hughes considers the technique and influence of a giant of the 20th century art world, Jackson Pollock…

Jackson Pollock kicked down the front door of abstract expressionism and continues to be a major influence, celebrated right now by Tate Liverpool, and forming a key part of its new exhibition.

Constellations, an extensive re-hang of the Tate collection focuses its attention on significant artists in their field, credits Pollock as one of nine artists whose work has had such a transformative effect on both contemporary and modern art.

In both obvious and more subtle ways, the creative hand of the American can be seen to have guided others, from sculptors to performance artists. But what was it about Pollock and his work that left such a legacy?

Born in 1912, Pollock’s early childhood was anything but conventional; moving state to state and suffering at the hands of an abusive alcoholic father. After his father left the family, the eight year old Pollock fell under the influence of his older, artist brother, who is credited with being the inspiration for his following a creative path.

Critics often remark on the transition Pollock made in his artistic style throughout the years, from the regionalist work produced while studying under Thomas Hart Benton, to the ‘drip and splash’ effect for which he became known. Pollock remarks that a turning point in his artistic direction coincided with a visit to a Picasso exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1939, giving Pollock the confidence to experiment.

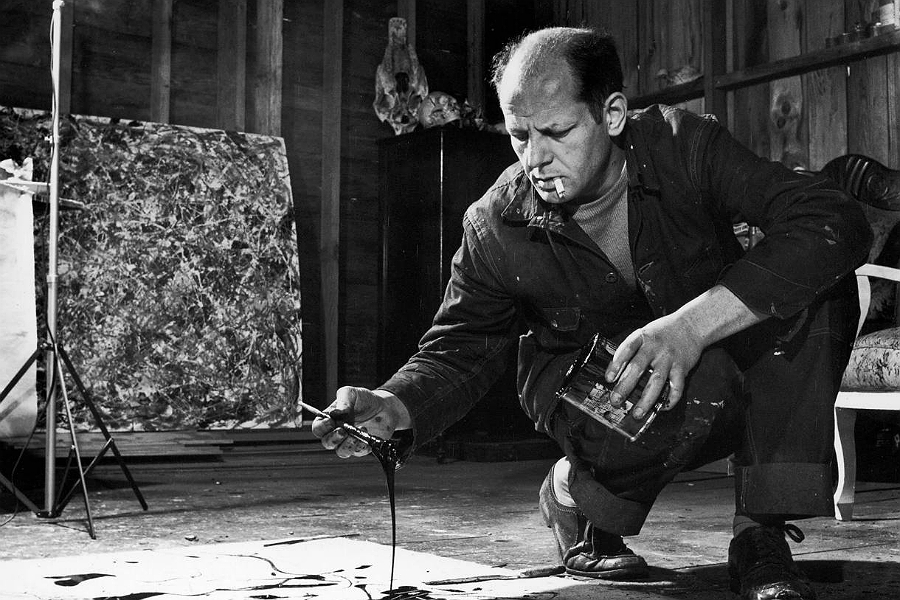

The ‘drip and splash’ effect and the associated action painting method was regarded as revolutionary at the time; focused less on the outcome of the painting than on the artist’s subconscious mind, Pollock once said that “Today’s painters do not have to go to a subject matter outside of themselves. Most modern painters work from a different source. They work from within.”

Attaching the canvas to the floor and hard brushes, knives, broken glass and even syringes being used to apply paint from all directions the new ‘all over’ style created what are now considered masterpieces. The critic Harold Rosenberg argued that Pollock and his contemporaries redefined the canvas as an “arena in which to act… What was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event”.

With no focus on a particular point of reference, Pollock’s work had a fluidity that helped make him the best paid avant-garde painter in America, leading Life Magazine in 1949 to ask: “Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?”

Tate Liverpool have chosen Pollock’s Summertime: Number 9A as the ‘trigger’ piece in the Constellations series, and it’s easy to see why as the spontaneity of the techniques used are so characteristic of what made him so famous. The painting, created in 1948, conjures images of the cool Atlantic breeze blowing through Pollock’s hot Long Island studio in summer with the black spindles mingling with the bursts of bright yellow, pockets of blue and smatterings of red.

Quintessential to paintings created in the drip style, there is an almost rhythmic quality to Summertime: Number 9A, with the layers of paint dancing across the canvas and becoming a field of action.

One abstract expressionist painter that followed in the path of Pollock, Willem de Kooning, said that he had “broke the ice”. Pollock moved art into new realms after 1947 and set the course for what was to come. By drawing together other abstract art which emerged after the drip painting revolution, the exhibition allows the viewer to see Pollock’s influence more clearly in the development of expressionism.

Artists stemming from the centre of the Pollock constellation, such as John Cage, Nigel Henderson and Robert Adams, each used different mediums to respond to the ideas of chance, automatism and performance which Pollock’s work encapsulated. Another, Stuart Brisley, as a reaction to the idea of the process of creating art becoming an ‘event’ or performance within itself, sought to challenge what he saw as the vanity of the artist in performance art.

Influenced by the Marxist counter-cultural movement of the 1960s, Brisley’s series of 12 photographs and 3 typescripts selected for this exhibition records his 1972 piece of performance art entitled ZL63595c. It documents Brisley’s 17 days living in a room of Gallery House in London were the audience were invited to look through a small hole in the wall yet not allowed to communicate with the artist.

The piece sought to emphasise the ‘body in struggle’ and the conflict between the human autonomy and the forces of the state. Linked with the work of Pollock is the sense of inherent primalism, with the idea of not knowing what the outcome would be when starting.

One of the wonderfully surprising aspects of Constellations is that the relationship of the trigger artist to those in their sphere isn’t always immediately obvious, and is highlighted perfectly here; the lightness of Pollock’s action painting style is in stark contrast to the darkness and vulnerability of Brisley’s expression of self degradation.

What is obvious is that Pollock’s work continues to influence and inform.

Conal Hughes

DLA Piper Series: Constellations continues at Tate Liverpool