Chagall: Modern Master?

The largest UK retrospective of his work for 15 years, Chagall: Modern Master seeks to redefine the painter’s place in art history. Does it succeed?

The erstwhile Time magazine critic Robert Hughes once called Marc Chagall “the quintessential Jewish artist of the 20th century”, and indeed, his heritage looms large throughout this exhibition.

But for Chagall: Modern Master, the first major UK exhibition of his work in more than 15 years, curator Simonetta Fraquelli steadfastly looks to reposition him on his own terms as a “pioneering avant-gardist”. For Fraquelli, this is an opportunity to present Chagall in a radically different way.

Emerging at the beginning of the last century in his native Vitebsk (now Belarus), his career took him around Europe and back to Russia, and in the years subsequent to his death (in 1985 at the ripe old age of 97) is – in many quarters – thought of as one of the best known and loved artists of the period.

That being the case, do we need to see him and his reputation reconsidered? Whether or not his reputation is in need of reappraisal, or indeed, whether this exhibition achieves it is, as in the case of art, entirely subjective.

Arranged chronologically (from 1911 to 1922) and in broadly thematic chunks (with titles like The Lure of Paris, and The Non-Objective World), it takes in more than 70 paintings and drawings from when he was still a young man. It’s astonishing, occasionally breathtaking, to see him embrace and respond to the various movements coursing through the art world of the day, encompassing Fauvism, Cubism, Suprematism and Constructivism.

A cursory glance may put one in mind of an opportunist, magpie-like artist, but this wouldn’t be quite right; it’s soon clear that Chagall’s work, while clearly responding to the world around him, retained a ‘selfness’. Certainly, there is no nagging suggestion of pastiche at play, more a respectful acknowledgement of trends while adding significant flourishes that could only be his.

An early, considerable, influence was Matisse, says Fraquelli: “as soon as he gets to Paris his palette lightens up.” She isn’t kidding; one only has to consider Birth (1910) – all dark hues and shadows – alongside work created upon his arrival in Paris in May 1911 to see the dramatic difference. Such was the manner with which he embraced this new palette, Picasso said of him that “when Matisse dies Chagall will be the only painter left who understands what colour really is”.

High praise indeed, and while this is just one quote (albeit from Picasso), it certainly helps in understanding why Fraquelli felt the world may have been missing something in Chagall. Up until now, that is. If Chagall ever felt overlooked or relegated at the hands of art history before, Modern Master rights that perceived wrong.

Walking through Tate Liverpool accompanied by the visually schizophrenic Chagall is akin to having a particularly vivid dream, only for it to flip to glimpses of a parallel nightmare and then back again. Playing into this sense of proximate unreality – Chagall himself claimed that he sought the logic of the illogical in his work – are pieces like Over Vitebsk, featuring a huge figure lurching over an otherwise ordinary snow-covered landscape (main image).

It has been posited that this figure could be read as a ‘wandering Jew’; decked out with walking stick and bag of belongings thrown crudely over his shoulder. The stark ambiguity of the figure’s great stature with the clear suggestion of relative poverty is a fascinating one in isolation, but Chagall often played with this duality.

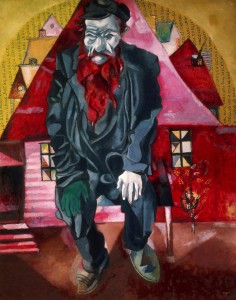

Moving through the gallery space into The Sense of Self and Jewish Themes section, one can’t help but be struck by Jew in Red (above). Ostensibly a homeless man with mismatched shoes, unkempt beard, blackeye and missing glove, he should make for a wretched study. Instead, Chagall has somehow imbued him with a quiet nobility.

It is here that Robert Hughes’ quote begins to make real sense – his assertion that Chagall was a quintessential Jewish artist wasn’t to damn him with faint praise, more an unavoidable response to the Russian’s work, born of his being Jewish at a very particular time in Russia’s history when the traumas of war and religious persecution were never far away.

That his heritage is writ large and wholly acknowledged here, providing one of the central hooks around which the exhibition hangs, this isn’t to say that it dominates in any disproportionate manner. Seeing the results of Chagall’s negotiations with the onset of Constructivism and Suprematism is nothing less than fascinating, and if his murals for the State Jewish Chamber Theatre fall a little flat in comparison, it is no less impressive to learn that these were produced during the upheavals of the Bolshevik revolution.

Reaching the final room of the exhibition, there is a welcome concession to his later work. As Fraquelli points out, “he did continue to be a prolific and successful artist, much loved by the public.” And in the likes of Red Rooftops (1953) and Saltimbanques in the Night (1957), you can see hints of why that would be the case.

With Chagall: Modern Master dealing predominantly with the period 1911 to 1922, we see how his work developed in commensurate fashion to the tumultuous historical and artistic climate. Fraquelli has clearly framed how he so vibrantly processed and reflected these changes, and in doing so, has gone some way to justifying her call for a radical reassessment of a 20th century great.

Chagall: Modern Master continues at Tate Liverpool until 6th October £7.50-£11.00