The Treachery of Images

In this essay, Nathan Richardson muses on facts and the impressions of facts, with specific reference to Fournier’s The Funeral of Shelley…

During my education, the Walker Art Gallery was often patronised as a suitable purpose for a school-trip. It was (in the eyes of the school): inexpensive, safe, and allowed for students to engage with “the arts,” thus having some educational value.

Packed onto buses and deposited into the city, were: the teaching staff, whose faces for the entire day would emote only a sincere look of concern; the obligatory, over-zealous mothers who volunteered to assist on occasion (but never really did anything except usher the students about), and the children themselves, who – understandably – viewed the occasion not as an opportunity to embrace the great masters, but as mere novelty.

Extracted from their usual locale, they became excitable, and from my memories every one of these trips was completely disastrous. A short tour would be given, followed by some absurd activity in which one was expected to copy a painting with pencil crayons; but then of course the gift shop would always offer more appeal, and before long the day would be over, with nothing achieved but exhaustion.

I don’t excuse myself from this attitude, and years later, the gallery still held little attraction. For me, the city fulfilled one need: inebriation. It was only when I moved back from University, and signed on the dole, that a vague interest kindled. Visiting in March of this year I spent an afternoon wandering around Liverpool, aimlessly stalking the streets – drifting into coffee shops, book shops, along the river, and then I breezed through the gallery before slipping away, back to the dreadful quiet of suburbia. (I think, actually, it was my interest in Philip Larkin that led me back – in a letter of his from 1950, to his friend Monica Jones, he wrote of his journey to the Walker, and the delight he felt in seeing John Brett’s 1858 painting, The Stonebreaker. Sixty-three years later, I found myself gazing at the very same work that thrilled the poet, and this trivial, ephemeral detail in turn thrilled me.)

When still an undergraduate, I attended a public lecture at a gallery in Nottingham. It was given by an American artist (whose name escapes me today). I cared not little for his work but I found myself at the lecture nonetheless, and distinctly remember him recalling his days as a Fine Art student in Harvard, and remarking: “I liked looking at paintings. Writing about them was beyond painful, but I liked looking at them.” This made an impression on me, as I felt very much the same.

So, back in March, it was with this almost superficial attitude that I approached the gallery. I would, on occasion, contrive some notional argument for what the painter intended to convey, the significance of specific features, perhaps, but mostly I delighted in simply how the painting looked, rather than what the painting meant.

The work that struck me most was The Funeral of Shelley (above), an 1889 piece by the French artist Louis Édouard Fournier. The piece depicts the cremation of the poet Percy Shelley, on a beach near Viareggio, after his death (in 1822) in a boating incident nearby. It shows the burning poet, with friends Edward John Trelawny, Leigh Hunt, and Lord Byron, at his side. While Trelawny and Hunt look down mournfully, Byron gazes out, almost as though he is posing, and I can remember feeling slightly amused by this, but didn’t stop to think what it might mean.

A month or so later, my friend mentioned the painting. Of the great many works in the gallery, she spoke of this one. We arranged to meet and observe the painting together. And so, a few days later, she showed me Greiffenhagen’s An Idyll, a piece discoursed upon in D.H. Lawrence’s first novel, The White Peacock and for her a personal favourite. A brief visit was paid to The Stonebreaker, and then excitedly we approached Fournier’s masterpiece. How bleak it looks, I thought – the colours are drab, lifeless. This is what I began to find so fascinating about the painting, and it is this subject that I wish to specifically address here. We know from contemporaneous documentation that the day on which Shelley was cremated was in fact a long, hot August day, and yet Fournier emphatically ignores this. I am interested in facts, and the impressions of facts.

In an essay for the Guardian, the brilliant Julian Barnes wrote of the even more brilliant Ford Madox Ford: “Ford once said that he had a great contempt for fact, while guaranteeing his accuracy as to impressions.” I think this is particularly pertinent with regard to The Funeral of Shelley. Fournier himself displays contempt for fact, but the impressions of those facts are astute. While in a literal sense, Shelley’s funeral happened on a sunny day, Fournier manipulates that truth for artistic effect. The sense of loss and mourning is reflected dramatically by nature Herself, the implication being almost that she herself weeps over the departed poet. This, of course, is hardly uncommon in the arts, often referred to as pathetic fallacy.

Is Fournier right to do what he does? In a word, yes. Art, I believe, should be a heightened version of life. Facts lack an interior. They are inhuman. But impressions are real, they are human. The impression conveys what something feels like, not what something is. The truth, more or less, is boring.

In our own lives, you can, for example, catch the eye of somebody passing you in the street and feel as though your entire world has been utterly moved. In truth, you have merely interacted with another, but the impression of that is much greater. Just as Proust, dipping his Madeleine cake into a cup of tea feels his history invoked: had he recalled his past through rational thought, the same memories, he would have been, I’m sure, unmoved, but it was the sensation of the cake, the impression of the fact that led him to feel, ‘that exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses’.

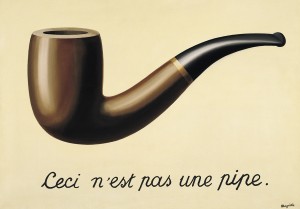

This idea of mimesis is one that pervades Literature. In The Republic, Plato writes of Socrates’ metaphor of three beds (ideas): the first bed is one formed by God; the second bed, a replica of God’s, crafted by a carpenter; and the third is one made by the artist and a replica of the carpenter’s. Several centuries later, René Magritte, in his painting, The Treachery of Images, evoked something similar, stating, beneath an image of a pipe, Ceci n’est pas une pipe.

There is no inherent relationship between these two works but both seem to suggest the inferiority of art to life. The artist’s impression of the bed is inferior to God’s, just as Magritte stresses that his pipe is not, in fact, a pipe. But the beauty of art, the importance of art, is that it can take themes, ideas, images, etc., and remove them from their ordinary context placing them into something greater. An artist takes an idea and transforms it from something everyday into something universal.

Magritte’s pipe may not be real, but it represents something real. It comes back to this sense of facts, and the impressions of facts. This is what I find so fascinating about The Funeral of Shelley. Fournier captured the impression of that day particularly. Of course, he could have written, ‘This is not a funeral,’ which would be literally true, but it is how the funeral felt – and feelings, I believe, are more interesting and more important than facts. They are what make us human. The purpose of art should not be to recreate life, but to explain it, and it is through impressions, I believe, that this is best achieved.

Nathan Richardson