Fréger & Stenram: Juxtaposed

Drawn to a pair of seemingly opposed exhibitions at the Open Eye Gallery, Stephanie Kehoe gets theoretical…

Until the past century, a big part of art’s history is that of gender inequality. With women not being recognised or allowed to have the profession of ‘artist’ until the nineteenth century, the art world had been dominated and shaped by male influence.

The Open Eye Gallery (as part of international photography festival, LOOK/13), showcases a pair of modern-day photographers who, ostensibly at least, occupy opposing sides of the debate. Contemporary French photographer, Charles Fréger, investigates the image of male identity through different cultural backgrounds, whilst Swedish counterpart, Eva Stenram, alters found images to tempt and challenge the theory of the male gaze.

Throughout Fréger’s work a theme is immediately evident, the use of the male. Although a diverse range of projects using collective and singular portraiture, the male is nearly always the subject. Fréger’s concept revolves around the pressures of a boy becoming his culture’s ideal male. In his project Wilder Mann: The Image of the Savage, Fréger exemplifies this by highlighting different traditions and rites of passage of men in more than 19 different European countries.

Although each culture may have a different process, both men and women will go through something known as social identity formation; this self-categorization is how the individual perceives their role in society, affecting their values, beliefs and behavioural norms. Another project of Fréger’s, Rikishi, is a collection of photographs utilising a photojournalistic approach. This time, the subjects are sumo wrestlers, in the sport’s native Japan, where he has captured the portraits of the sport’s super-stars in waiting. In a cultural contrast to the Wilder Mann series, Rikishi highlights a mix of prepubescent boys and young adults in traditional sumo dress, and in notorious Fréger style, takes the subjects out of their context and captures them in a studio space.

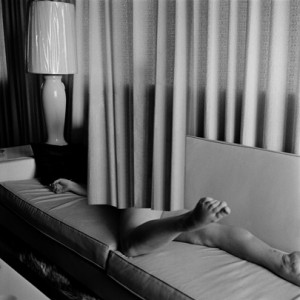

Challenging Charles Fréger’s male dominated exhibition, Eva Stenram’s photographic project, titled Drape, consists of a number of found vintage pin-up images which she has altered by covering the women in an extension of the curtains shown in the photograph. By making the original intended background become the foreground, as well as covering up the models nudity, the erotic mystique is heightened for the viewer. By purposefully directing the viewer’s gaze at a feature of the photograph which isn’t usually the main focal point, Stenram offers a reflective point of what our gaze was expecting and compares it to what is now hidden – our imagination in what lies behind the curtain.

These nude pin-up images from the 1950’s and 60’s, it goes without saying, would by-and-large have been produced for men, by men; originally pin-up was created for the attention of the troops during the Second World War. Knowing this information, we are already expecting something from said photographs – without seeing them, we have a good idea of what they should look like. When this certainty is removed, we are left to reflect on our expectations and what they might represent.

Of course, it was feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey, who coined the term of the male gaze; that men were in control of the camera, and as a consequence, objectified women. Stenram counter-balances this by obscuring or totally hiding the thing intended solely to entice the male – the female form. The artist plays on this well-known term to make the voyeur aware, both of what they are expecting from the photograph, and perhaps their complicity in the process.

Both of the exhibitions deals with ‘the male’ differently, but the approaches are inextricably linked; Fréger captures different cultural contexts and stereotypes that a male must fill in his society, whereas Stenram challenges the male gaze by concealing originally nudity, thus letting imagination lead the way. These artists, perfectly juxtaposed here, make for a fascinating and thought-provoking pairing.

Stephanie Kehoe