The New Czech Cinema

Watch out Romania, the Czech New Wave is coming…

When we speak about new wave in the context of cinema, one’s mind will most readily (almost invariably) leap to names like Jean-Luc Godard and Francois Truffaut, figureheads of the French Nouvelle Vague of the late 50s and 60s. But the term isn’t exclusive to that most fruitful period of productivity for our cousins francais.

Around the same period (early ‘60s-‘70s) Czechoslovak cinema was enjoying its own renaissance. Led by students of the Film and TV School of The Academy of The Performing Arts in Prague (FAMU), the Czechoslovak New Wave was, it could be argued, primarily one of dissent at the hegemony of the communist regime in power at that time rather than any hegemony of aesthetics and practice.

Though garnering international recognition and spawning a pair of Academy Award Winning directors (Jiří Menzel and Miloš Forman) in the process, the movement’s initial intention was “to make the Czech people collectively aware that they were participants in a system of oppression and incompetence which had brutalized them all”.

Flash-forward a generation or so and you come to 1982 and this Thursday’s screening of Walking Too Fast (Pouta), directed by Radim Špaček. The film, which looks at a Czechoslovakia once again in the grip of an imposed regime, heralds the start of the Made in Prague, New Czech Cinema UK Tour 2013. Now in its fourth year, the tour is a dedicated showcase of contemporary Czech filmmaking, and features five award-winning films. It makes for a fine way to demonstrate the current crop of directors, and no doubt the Czech Film Center – understandably – are clamouring for a way to package its very own modern-day new wave.

For that to happen of course the films have to stand up to analysis, and first signs are promising. Going back for a moment to the first of the films to screen, Walking Too Fast suggests echoes of the wonderful Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck film The Lives of Others. Focusing on Antonin, a member of the secret police who yearns after the wife of an assigned subject, the film seems to have all the hall-marks of a classic, yet fresh take on the cold war thriller.

Screening next week, Long Live The Family appears to offer something of a change of pace, but this family strife drama cum road movie is no less compelling for it. Central to the story (and allegorical stand-in) is Dad Libor, who we’re told, represents “the archetypal small nation swept up by market forces” that is the Czech Republic. It’s a fascinating conceit, one which we hope is done justice by director Robert Sedláček.

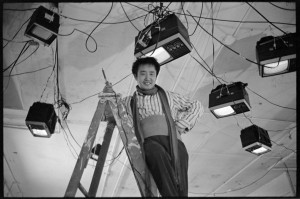

Next up and perhaps the film that has captured our attention most (due in no small part to the dazzling use of rotoscoped animation, which helped it win the European Film Award for the Best Animated Feature last year) is Alois Nebel (pictured above). At the tail end of the ‘80s, ostensibly unremarkable loner Alois works at a small railway station, but of course, there’s more to him than at first meets the eye. Haunted by a dark past, one which catches up to him fast, Alois ends up in a sanatorium, which is where his story really begins.

More a straight look at the conflicts within a family than those of a country in transition or attempting to bury damning secrets, Zuzana Liová’s The House (25/04) is a tale of cantankerous Dad Imrich and his endeavours to hold on to his youngest daughter after a fallout with his eldest leads to her being disowned; a course of action one suspects will not end well.

The final film in the selection is Lidice, screening on the 2nd of May. Dealing with the circumstances of Nazi Germany’s only officially recognised act of genocide during World War Two (in the village of Lidice), director Petr Nikolaev lets the inhabitants tell the story, using their day-to-day lives to provide insight into the forthcoming catastrophe and its aftermath where, as we are shown, sometimes surviving can be the worst outcome.

Speaking of outcomes, whether or not this batch of Czech cinema constitutes something one could describe as amounting to a new wave is open to debate; only time will tell of course, but the films and their directors certainly merit further investigation, and this bite-sized tour presents audiences with a perfect opportunity to do so.

Made in Prague: The New Czech Cinema UK Tour begins this Thursday @ FACT with Walking Too Fast