What is Gummo?

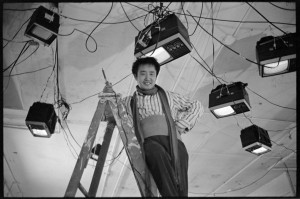

DW Mault contemplates Gummo, which screens at Metal tomorrow, and its maverick director Harmony Korine…

I want to convince you to experience the unknown, that nothing will ever be the same. The hardest thing is to change perceptions, to drag someone by the scruff of the neck and say “here it is”… Well here it is: Harmony Korine’s debut film Gummo.

“If an actor is a crack smoker, let him go out between takes, smoke crack, and then come back and throw his refrigerator out the window! Let people feel they can do whatever they want with no consequence. I wanted to show what it was like to sniff glue. I didn’t want to judge anybody. This is why I have very little interest in working with actors. [Non-actors] can give you what an actor can never give you: pieces of themselves.” – Harmony Korine

To attempt to describe something so pure, so great does it a huge disservice. If you’ve never heard of Gummo, I envy you, because on Friday at Metal Gallery (Edge Hill station) you get a chance to have that experience. Selected by Liverpool filmmaker Ged Hunter, whose second film Leonard (which appeared at FACT’s Liverpool Short Night,) will precede the main event. Gummo is the first in Metal’s 2013 film season that will run on Fridays until March, and will include: One Eyed Jacks, Chinatown, Pandora’s Box and The Passion Of Joan Of Arc.

“I grew up in the cinema. Buster Keaton changed my life, I realized that there was something so pure, there was a kind of tragic beauty that I had never seen before, and it was so moving and so big, what could be more amazing than what I was seeing…? So for me there was almost something holy about the cinema. My life is always 50 percent watching movies and 50 percent living life. Living life is always more interesting than films. I find life is more exciting, because it’s limitless. Films can only imitate life. They can only go to a certain point and then life begins. Watching films, I started to realise that they are all starting to seem the same. That they all have the same kind of humor, the same kind of actors, the same kind of characteristics, why is that? And I started to realise that everybody is going to these film schools and these are all people, who, 15 years ago would have gone to doctor’s school and now they want to make movies. None of them have any kind of stories to tell. All of their films are about this kind of process, about this generic kind of storytelling. More than anything, the great films are about life. There was once a day when cinema had glory. When John Ford was making movies, and Fassbinder was making movies, and Cassavetes, when there was glory ‘cause films once had the essence of life to them. And then something happened. I felt that film school was this place that was only teaching people to be technicians. And to think the same, have the same sense of humor and the same stories, and I realised that all you ever need to be a filmmaker is to watch films. I understood this at a young age.” – Harmony Korine

Cinema attracts the disaffected, momma pleasers, recyclers, fame for the sake of fame seekers, careerists, etc so when someone who arrives that genuinely wants to foment, who aims a plague on all your houses of the safe, the mediocre and the banal; he must be praised and pushed to the front of what Werner Herzog called the army of cinema, for which Harmony Korine is very much a good soldier of.

He is a filmmaker, artist, musician, prankster and actor… He’s all of these things and none of them; he is someone whose very existence becomes his masterplan: that is to infiltrate his uncommercial, uncompromising agenda – a pure vision – into the mainstream (not one for sitting on the sidelines).

“America is all about this recycling, this interpretation of pop. I want you to see these kids wearing Bone Thugs & Harmony t-shirts and Metallica hats – this almost schizophrenic identification with popular imagery. If you think about, that’s how people relate to each other these days, through these images. I wanted them to seem like homeschool kids… sort of guessing and coming up with these hipster things. They almost make a home school hip language. I wanted this inbred vernacular.” – Harmony Korine

What is Gummo (the name is never mentioned in the film; and referenced the unknown Marx brother)? Gummo is a film where the unknown is round the corner; you’re never aware what is happening or is going to happen (in a similar vein to Leos Carax’s Holy Motors), a snapshot which has no interest in moribund concepts like plot and structures. The storytelling is non-linear in the extreme, very much a series of loosely linked vignettes that take place in a tornado ravaged town called Xenia in the state of Ohio. The film that Korine wrote before Gummo, Kids (directed by acclaimed photographer Larry Clark), took inside 24 hours in the life of a mixed bag of NYC teenagers and their interaction with sex, drugs, alternative lifestyles and HIV; Gummo is the inverse, Xenia is small-town USA: run down, rural (KIDS was urban), where we peer behind closed downs to unjudgementally observe handicapped sex, breast cancer, teenage transvestitism, paedophilia and racism. How we feel about what we’re seeing (are we even supposed to see?), is in our hands, certainly Korine has no interest in holding our hands and telling us what to feel. For him a moral stance defeats the object of art and existence.

“I feel documentary always falls short. I think cinema verite is a fallacy, that the documentary is manipulated, there’s no such thing as truth in film. The idea that Godard said about 24 frames of truth, was always for me the ultimate lie. It’s just 24 frames of lies. But the best cinema to me works on a kind of theoretical level where it’s 24 frames of sort of truth. For me, being a writer and an artist and a viewer, the only thing I’m interested in is realism. If it’s not presented to me in a way that’s real, with real consequences, real characters, I have no desire to see it, because then it’s fake. It’s a cartoon, and I just don’t care about that stuff. But at the same time, in this ultimate search for truth, for realism, I know it’s impossible to attain, so what do you do? It’s like Gummo, people say, ‘Oh! My God, it’s got no script.’ And there’s a total script. But that’s what it is, a trick. Everything is presented as if it’s real, I’m manipulating everything.” – Harmony Korine

Cinema is in constant argument with itself about what it is/isn’t. Well Gummo is everything I hope for in cinema. Cinema that doesn’t force feed you an idea of how to live and forces us all to join in together in a homogenised mess forever and again (repeat after me). Gummo’s transcendental imagery stays inside your consciousness and will keep attacking you months after you first experience.

“The idea of being a pragmatist or being a worker doesn’t appeal to me. It’s only about great artists. For me, it’s certain directors, or maybe certain films that have influenced me. Of course, the most interesting career is Fassbinder’s career because he was working at such a rate, such an intense level… One year he made nine feature films. He was famous for saying that his films were like a house: Some were wood floors, some were walls, some were the chimney. At the end of his life the whole idea was that he could he live in this house of his work and I love that idea. The two things I remember about films: It’s characters and certain scenes. I never remember plots; I never remember the whole thing – I only remember specifics – and Fassbinder was so great because there are certain scenes that he would show you that no one else would give you.” – Harmony Korine

Lindsay Anderson always said “Never apologise, never explain”, and these problems (in Gummo) are never apologised for or explained, whether they be a Down’s Syndrome girl who shaves her eyebrows because she thinks it makes her look more beautiful; a midget who arm wrestles a big bear of a man and wins; a deaf couple arguing through intense hand gesticulation; teenage boys killing cats so they can buy glue to get high; an albino waitress in a car park describing what she finds attractive about men; three extremely young white trash sisters get touched up by a middle aged man. It’s a miasma of original thought; part poetry, part bullshit, part (true) youth rebellion, and in Harmony’s own words a “complete genre-fuck”. There’s no cynicism or po-mo irony here, only a form of meta-realism that is most definitely social anthropology.

“I’m a 100 percent commercial filmmaker. I have nothing to do with independent directors, alternative cinema. I make Harmony movies. It’s a cinema of obsession and passion. But at the same time, I can’t differentiate between notions of underground. Underground film, underground music, alternative culture, to me it doesn’t exist. To me the future is either good or bad and it’s kind of making sense of both those things. Like the film – I involve scenes and situations that are the scenes that I love. It’s only scenes and images that I wanted to see, with no real explanation. Nothing coming before it. So getting back to the question, I was basically free to make this movie this way, which is a miracle. Because what’s on screen is a pure vision. The way things are structured is that people leave me alone. I have nothing to do with anyone. I have no idea about how other people make their movies. I don’t make very much money. I don’t concern myself with others. I don’t fraternise with the enemy. I just work, and I love and I fight and I just do my own thing. So I am making this film and I finish editing and it has to go before the ratings board. The only stipulation in my contract with the studio Fine Line is that I had to turn in an R rated film. Basically, in America, few studios will distribute NC-17. NC-17, in the States, is a kind of word for X. Basically, that’s because 75 percent of the theaters in America won’t accept the film. 95 per cent of the video chains where you make half your money won’t accept it, like Blockbuster. You can’t advertise on MTV. You can’t advertise in 90 percent of magazines or newspapers. So right there you’re limited.” – Harmony Korine

Shot in Nashville, Tennessee (Korine’s hometown), Gummo features only four actors; Chloe Sevigny, Linda Manz, Max Perlich, and Jacob Reynolds in an ensemble cast of over 40 speaking parts. The lives of the local people, old school friends and acquaintances, are seen through the cinematography of Jean Yves Escoffier (who has sadly passed away) who worked most closely with Leos Carax.

“We’re essentially seeing the kind of poverty that we’re used to seeing in Third World countries when news crews are covering famines, [but] seeing that in the heart of America. One small home housed fifteen people and several thousand cockroaches. Bugs literally crawled up and down the walls. At times, the crew rebelled against filming in such conditions and Korine was forced to purchase Hazmatsuits for them to wear. Korine and Escoffier, who thought this was offensive, wore Speedos and flip-flops just to piss them off.” – Cary Woods, Gummo Producer

Don’t not take my word for it, Gummo and Korine have been championed by directors Jean Luc Godard and Larry Clark, and earned the congratulations of Werner Herzog, Lars von Trier and Abel Ferrara. Gus Van Sant perhaps sums it up best: “Venomous in story; genius in character; victorious in structure; teasingly gentle in epilogue; slapstick in theme; rebellious in nature; honest at heart; inspirational in its creation and with contempt at the tip of its tongue, [Gummo] is a portrait of small-town Middle American life that is both bracingly realistic and hauntingly dreamlike.”

All this and I haven’t even mentioned the amazing soundtrack that unifies both death metal and Roy Orbison…

DW Mault

Gummo screens 6.30pm @ Metal Gallery on Friday