Harangue the DJ

How to achieve a vibrant, successful club night in the face of requests for the ‘same old, same old’? Mikey Stevenson spoke anonymously to a number of city DJs to find out…

Soon after returning from a year in Berlin, a city renowned as a centre of European youth and pop culture and much loved by scousers, I met with a friend for a drink and catch-up in TriBeCa (Berry Street). Named after the New York City artist neighborhood of the 1970s, you might be forgiven for expecting some Patti Smith, Talking Heads or dare I say it, even Sonic Youth on the turntables, but no. On this occasion, a ‘wedding party playlist’ of ABBA, Stevie Wonder and The Proclaimers had been deemed better, more apt, more in keeping with the clientele. The only NYC band with a hope in hell of making the playlist was Blondie (and only then, Heart of Glass).

TriBeCa should not be singled out, after all, they are only playing what most of the other bars are playing. I was reminded of the 2011 Boxing Day party in Shipping Forecast (Slater Street) which included an MC Hammer heavy mix-tape that wouldn’t have been lost in Flares or The Reflex. Odd for a venue with a notoriously selective door policy, a venue that has seen the likes of Delphic and Marc Ronson DJ.

On returning from my extended time away, it has become clear that Liverpool bars are, for the most part formulaic, unimaginative and risk-averse, even when they portray a different image. There are many factors that may be at root of this problem: bar manager fears about profits, customer intolerance of less mainstream music, lazy DJs, nostalgia. I interviewed a number DJs with extensive experience of performing in various Liverpool venues and bars to get their opinions.

I was surprised to hear that very few venues have outlined their music policies. “I’d never play somewhere like that, most of the venues I’ve worked with wouldn’t interfere with what I play”. Developing nights with specific audiences in mind, and then hiring DJs that suit it, is the process by which venues usually acquire an informal music policy. “Promoters usually do a good enough job to let people know what the music is going to be.”

Any negative reactions to the music is usually aimed at specific tunes/bands, and reactions can be extreme. “I’ve been bollocked for refusing to play Guns N’ Roses and I got told to turn off Oasis half way through a song by a bar manager. He told me it was shite (it was) and I had to play Bandages by Hot Hot Heat instead. I did. It cleared the dance-floor and the night was over.”

Any intolerance shown by the manager is typically a reflection of their customer’s taste. People will not stay in a venue if they’re not enjoying the music, and any decent manager will know their regular crowd. “The main problem I’ve encountered is venues wanting an ‘indie’ or ‘alternative’ DJ with little grasp of what that means. Their regular customers are sort of going: ‘What the hell is this?’ and you feel that you’re going to die on your arse unless you play Lady Gaga.”

The feel of the venue is not something owners must begrudgingly live with; it’s something they’ve cultivated and it can be a difficult thing to change, especially if the manager is out of touch with current trends. Venues more on-trend, and those that have consciously cultivated a more tolerant crowd, can afford to be bolder. “Korova were incredibly supportive, even when they didn’t like what I was playing. I got (maybe once) a gentle nudge not to play soul.”

The dominant force is, rather unsurprisingly, the customer. Crowd intolerance ranges from passive (“I’ve cleared rooms before”) to aggressive (“I once had an irate young lad who spent a good hour angrily scrawling ‘PLAY INDIE’ on scrappy bits of paper for me. He then went home and sent me several abusive Internet messages, which I couldn’t possibly repeat…”) and occasionally resembles something from a crowd behavioural study.

“I once took over a night from Clint Boon at very short notice and a group of lads who’d travelled over from Manchester were less than impressed. They danced for a bit and then when they realised I wasn’t Clint Boon, stood at the front of the stage chanting ‘Boon Army!’ at me for half an hour, then left. Which was nice.”

Regardless of how much they complain about the ‘same old, same old’, customers betray their genuine tastes, particularly after a few pints. “People are going out to pull or to have a drink with their mates. They don’t want anything to interfere with that.” The DJs perceived effect of this was generally quite pessimistic. “The nights and venues that prize experimentation don’t last. It isn’t a viable economic model. The places that do well are fairly lowest common denominator. I mainly just think there isn’t enough of an audience to keep places that are risky open.”

However, I feel that club-nights are not facing challenges due to a limited audience, but as a result of the introduction of late licensing for bars. The extended opening hours for bars is a challenge to venues and club nights. Consequently, they are only busy for a couple of hours each week. “I used to enjoy going to the clubs early and hearing new stuff, music that you couldn’t buy yet, because the DJs had promos sent to them. Today anyone can get their hands on new music, so that’s not an added appeal any more. It’s great that music is more accessible to everyone, but you still struggle to get a good response to it. By the time people have paid into the clubs now, they’re usually rather jolly and aren’t interested in new stuff, they just want music they know and can dance to. But on the other hand you’ll still find people criticising DJs for playing ‘the same old music’. It’s difficult to find a balance.”

Listening tastes of customers in Berlin are very different to those in Liverpool. Customers don’t want to appear to have populist music tastes and expect the music to be unfamiliar, even challenging. In this city of constant change, people easily grow weary of repetition. Its also a city so weighed down by (and uncomfortable with) its past, people are potentially more forward-looking and less nostalgic. Conversely in Liverpool, a city that thinks it invented rock and roll, people want to hear the same tracks in bars because it makes them feel nostalgic and proud.

A taste for repetition that is not shared by most DJs. “I find it alien that they are so determined to hear it again, and usually it’s ‘RIGHT NOW’ that they want you to play it. I can’t even hear my favourite song in the world more than once a day without getting irked.” The city frustrates some in its taste for nostalgia, but also given that Liverpool has experienced very little change until recent years, a taste for repetition surely isn’t a surprise. “A friend of mine made a really good point a few months back: The people who approach you and so desperately ask you to play the buzz song of the hour, have usually heard that song already 3 times that day, and they probably asked for it to be played in the last place they were in. They probably listened to it on repeat as they were getting ready to go out.”

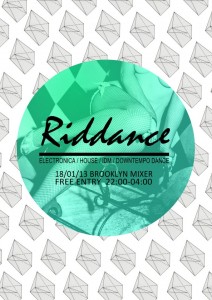

Though it is unclear if things are beginning to change, there have been some positive developments. Bars that specialise in playing more interesting, less nostalgic music have seen some degree of continued success. Mello Mello (Parr Street) excels in playing music most people have never heard before. The Riddance night at Brooklyn Mixer (Seel Street), which plays a downtempo electronic mix of Gold Panda, Burial, 4Tet and more, shows real promise of being a successful left-field DJ night. Some of the more established venues have found the confidence to challenge their own music policies with varying degrees of success.

“I’ve been getting sporadically booked for a place out of town lately, who are eager to turn their place around. They’ve been pretty bold and changed their music policy to no longer include chart and cheese. The punters are taking a while to come around to the idea but it’s working, for the most part.”

Perhaps the ‘most likely to succeed’ of the newer venues is Sound Food and Drink (Duke Street). A self described “place to sit-off”, the owners have combined elements of the Liverpool indie scene with those of American dive bars and Berlin cafés. The result is a cozy, welcoming space. You feel you could be at home listening to your own tunes, even when they’re playing something new. This hybrid approach hugely extends the potential flexibility and sustainability of a venue. However, if these flexible spaces are the only venues to survive long term, then effort must be made to prevent the music from becoming incidental. It’s reassuring then, that Sound plan to expand into their basement, providing a new immersive space, hopefully in the not too-distant future.

If customers want to listen to good music on a night out, they must support the venues that are willing to take risks. The survival of BBC 6 music against proposed closure has demonstrated that alternative platforms can continue if their supporters back them up. “There should be a way to get people more involved in the music that’s played at club nights and encourage them to listen to new music, so it’s not just the same stuff all the time. I think there are a lot of innovative nights in Liverpool right now that are trying to do that, and people should support them more, instead of heading down the cheap bars to sing along to an Oasis CD.”

Mikey Stevenson