Tracing the Century: Drawing as a Catalyst for Change

Linda Pittwood tours a sexually charged and meditative exhibition and asks: is drawing having a moment?

If this exhibition was to come up with a definition of drawing – which it deliberately hasn’t done – it would explain that drawing, unlike painting, isn’t intrinsically linked to a medium. Instead, drawing is a deliberate attempt to represent something. This ‘thing’ does not need to exist (although it can do or have done) it can be imagined or remembered, or it could be an idea or a concept, but the drawing after the thing always remains, as traces.

This exhibition is Tracing the Century: Drawing as a Catalyst for Change at Tate Liverpool, curated by Gavin Delahunty, its Head of Exhibitions and Displays, and by Katherine Stout, curator of British contemporary art at Tate Britain. Both have extraordinary credentials in the field of drawing: Gavin was curator at Middlesborough Institute of Modern Art (mima) and Katherine co-founded the Drawing Room, in London in 2001. With this just one of a number of recent blockbuster shows on promoting drawing. The question is: is drawing having a moment or is this the beginning of a permanent change in status for works on paper?

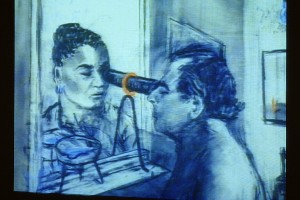

Downstairs my viewing experience begins in a darkened room accompanied by the fuzzy hum of a projector. This is a display running alongside the main exhibition; a new commission by Matt Saunders called Century Rolls. To create his images, Saunders shines light through paintings or other barriers onto photosensitive paper. The result is the first of many examples of drawing embedding itself in modern art making processes. Besides his photographs, Saunders creates animations; which, in spite of their monochrome palette reminded me of fauvist art – a branch of Impressionism characterised by bold colour and blocky brush strokes.

Upstairs for the headline show, the fauvists make another appearance, represented by Paul Klee. Almost straight away his drawings make me think about music, and all that mark-making can communicate. The marks on the paper are almost making sounds in my brain. Klee is part of a selection of four artists (along with Paul Cezanne, Richard Hamilton and Lee Bontecou) whose work is shown together. The quirk of this exhibition is that the interpretation hinges on these groupings, rather than picking out themes. Gavin describes the timeline of the exhibition as leaping “back to the future,” as it links pieces with theoretical and visual sympathies rather than in any way acknowledging their chronological order.

The exhibition tries to trip up its visitors with sculpture, new media and even little bits of paint. The piece that blows open the debate about what drawing is, is Henry Moore’s Recumbent Figure. It isn’t a very large example of Moore’s work in stone, but it is nevertheless monumental. It is possible that the sculptures are here as a curatorial device to ‘lift’ the show; as well as or instead of because they really are drawings. However, Gavin explains that they have put sculpture in, “second place,” and by placing it alongside unexpected comparative pieces given it new meanings. Moore is part of a “sexually charged” selection of works including pornographic images by Cornelia Parker, feminist art by Hannah Wilke and intimate pen and ink drawings by Andy Warhol.

Tracing the Century also uses some unexpected language to give a sense that the drawings can hold their own: ‘robust’, ‘aggressive’, ‘urgent’, ‘confident’, ‘weaponry.’ But what the show doesn’t do is turn its back on or undervalue the fragile and ephemeral qualities of works on paper. The intensity of the emotional response by the curators is no more apparent than when Gavin describes how seeing one of the pieces emerging from its crate “moved” him. And the process of Julie Mehretu drawings he describes with awe and wonder: “the artist is trying to capture something cerebral about existing and breathing in and out, and she’s tried to capture that with graphite, on paper.”

Both curators were really excited to show me the work of Sir William Orpen. An image of his work was used to market the exhibition, and the ideas and strands of the exhibition all seem to come from or go back to his oeuvre. Only recently acquired by Tate, “although they have been known about art-historically for a long time,” says Katherine. The drawings were produced to aid the study of medicine at the end of the 19th century, which demonstrates “that art might be made for one purpose and now we see it in a different way… and yet,” Katherine enthuses, “they look incredibly contemporary.”

Tracing the Century demonstrates a legacy of the recent Tate Liverpool exhibition, Turner Monet Twombly. That show took the same risks in showing historic, modern and contemporary art together (something Katherine says is: “quite hard to do… but there is a curatorial and public appetite for it”) to tell a new sort of art historical story that has little to do with style or ‘ism.’ In that show abstraction and figuration (as in Tracing the Century) was under the microscope and both shows demonstrate how lines of inquiry are passed from generation to generation.

This exhibition has given Gavin the chance to revisit the “phenomenal collection of drawings” at mima. His former employer holds a world class collection of American post-war drawings, some of which will become part of Tracing the Century when the show tours there after its showing in Liverpool. This will potentially create “new relationships” between exhibits as well as offering something new for audiences who have already seen the show at Tate.

Tracing the Century has created a meditative space; where visitors can learn that drawing can be durational and powerful, as well as ephemeral and emotional. After seeing this exhibition it is hard to think of visual art without drawing as a backbone. Perhaps the traditional low regard for works on paper is the reason that there are still plenty of new ways to interpret drawings, by artists but also by arts organisations through their exhibitions and curatorial emphasis. It remains to be seen whether drawing will take up its place at the heart of art discourse, but the story of drawing is evidently ongoing.

Linda Pittwood

Images courtesy Tate Liverpool