My Cherie Amour

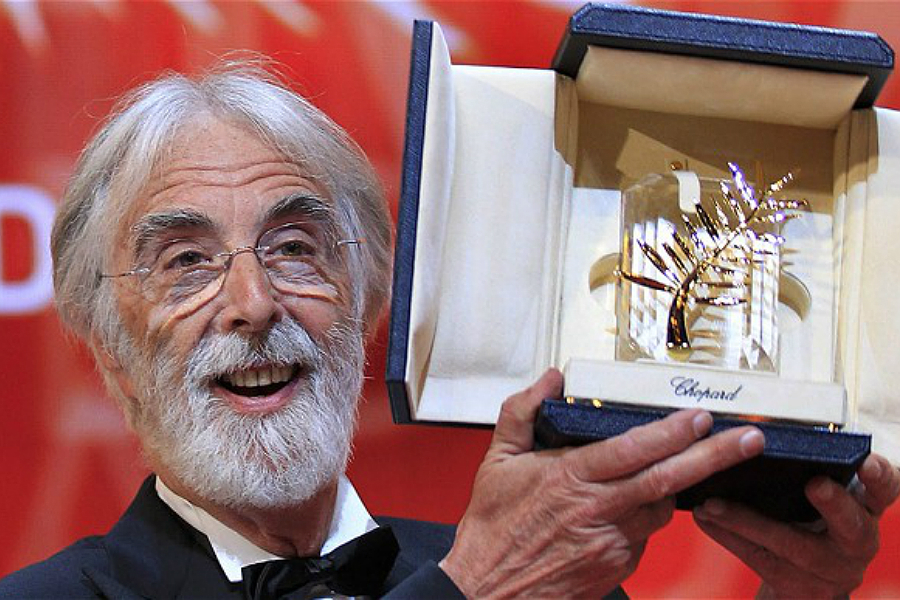

DW Mault writes a (kind of) love letter to Michael Haneke, the creator of Amour, the film which won him a second consecutive Palme d’Or…

Haneke, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Han-a-Ka: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Han. A. Ka. He was Haneke, plain Haneke, in the morning, standing six foot four without a sock. He was Mike in slacks. He was Haneke at Cannes. He was Michael Haneke on the dotted line. But in my mind he was always Haneke. Did he have a precursor? He did, indeed he did. In point of fact, there might have been no Haneke at all had I not loved cinema (with apologies to Vladimir Nabokov) …

It’s ironic with certain masters that it would be more surprising if they made a mediocre film than a masterpiece, but Michael Haneke, that monk of despair all dressed in black with the silver beard is one of those masters. What do we expect, when we expect Haneke? Do we take him for granted? It seems in some poly-perverse Anglo-Saxon nightmare (where I find myself) the backlash against Amour has already started. Beyond strange, in fact this position exists to emphasize how out of touch we seem to be in the Anglo-speaking world. It points us to question what is cinema for? Why do we exist, and are we interested, or do we clamber through the darkness to be distracted by those bright lights, while the reality that is evolution’s grand joke of a nightmare attacks the eyes we cannot see from.

Slavoj Žižek proclaims that cinema is the ultimate pervert art, because it doesn’t give you what you desire: it tells you how to desire. Again this brings us back to Michael Haneke and his latest film Amour. Desire is a word not formally connected to Haneke, why is this? Because the unblinking will tell us he’s a cold filmmaker who doesn’t care much for humanity. Piffle, it’s because he doesn’t sugarcoat the constant battle of daily existence in Hallmark greeting card platitudes that shows us the uncomfortable truth of the lie of existence: the idea of God’s lonely man. In fact Michael Haneke seems to come directly from another misunderstood foreigner assigned to Teutonic ideals: Thomas Wolfe; and his idea that loneliness, far from being a rare and curious phenomenon is the inevitable fact of human existence and is the default position for everyman.

Amour is Haneke’s second consecutive film to win Cinema’s highest accolade: the Palme d’Or. It peers at an elderly couple: Georges and Anne (someday someone will write a thesis on why Haneke repeatedly has characters in his films called Georges and Anne) and the effect Anne’s stroke and oncoming dementia has on their lives.

When Pablo Picasso said that art is the elimination of the possible he might have been talking about the very basis of formalist cinema. What we perceive is the elements that exist, to be; in the here and now. Haneke pushes us towards the idea that the physical reality of the world and what it means to inhabit it is at the point of the precipice is a surprising cosmic joke – only no one is laughing, because no one is there. We are only completely alone: “Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stage, and then is heard no more: it is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.”

George’s reaction to the slow disintegration of Anne is to lock themselves away and stoically be, just be. As we watch the unwatchable, we are able to see how reason has attempted to make us couple as a bulwark against existence. Ultimately, this is useless, as we will die as we were born: completely alone. The reason, this sleep of angular reason breeds monsters. The monsters of duality: Love/Death. Death/Love. Do we love to combat death or do we seek death to escape the love that we weren’t lucky enough to find? As in all great masters, Haneke has no answers, only Socratic questions. Questions that we as individuals must all ask ourselves, and puzzle our consciousness with the different answers we get every time we ask the question.

At the end of Amour (the film and the concept), we find Georges (and ourselves) after the bizarre emotionless first encounter with the great scythe, which leaves him (us) reeling from the indifference, the sense of loss ever growing, soured, devoured, belched and finally purified into what is now the eternal certainty of grief, ignorance and the mystery of love.

So go and see it for what it is, Cinema. Cinema not a movie, not a flick, just Cinema: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Cin. A. Ma.

Amour screens @ FACT from Friday and was reviewed at the London Film Festival

DW Mault