Orphée @ Metal – Previewed

Adam Scovell looks back at Jean Cocteau, a director who survived the tearing up of the rule book by the French New Wave…

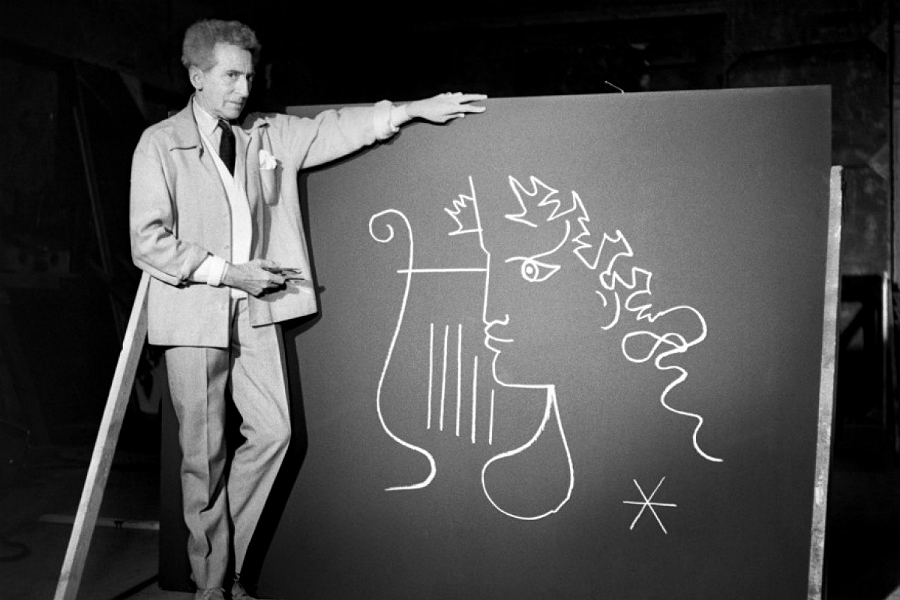

One of the directors of cinema’s old wave of French film to survive the slamming from François Truffaut and the Cahiers Du Cinema group, Jean Cocteau and his film work is, like the man himself, a whimsical oddity. Being good at just about every field and medium of art he put his hand to, Cocteau is a poet whose work and ideals are best realised in the medium of film, making him one of the great visual poets as well as a great director.

His reimagining’s of tales from the realm of fantasy are at once both timeless and distinctly of their time. 1950’s Orphée is the perfect example of this, with effects that are still beautiful to look at but a film clearly made in a world ravaged by the Second World War. The autobiographical nature of the majority of Cocteau’s work is perhaps one of the reasons why his opponents were so violently opposed to it. Transplanting a classical Greek legend into a work of clear autobiographical resonance could (and indeed was), perhaps be seen as arrogant, though it appears naively so rather than intentionally.

Orpheus is turned from the lyre player of mythology into poet in post-war France, who becomes obsessed with a princess dressed all in black. The fantastical nature of the work doesn’t become apparent until at least twenty minutes in, and as soon the barrier of reality is broken, the film takes joy in making sure that nothing is a certainty in this odd world. Mirrors become liquid gateways to the underworld where the dead work for beauracrats and live in a dishevelled and battered place, while angels of death take the form of two mysterious bikers.

The film screams of a handful of themes all coming from Cocteau himself. His lover Jean Marais plays Orphée with a typical arrogance well suited to a busy and well-known poet, but there’s more Cocteau here than just simply changing the mythology’s artistic endeavours. A general theme of sacrificing love becomes apparent when various feelings d’amour spring up between characters both alive and dead resulting in loss for both parties concerned.

Elsewhere Cocteau’s position in Nazi occupied France is addressed through a trial sequence (again later returned to in his final feature film The Testament of Orpheus (1959)) starkly resembling the collaborator trials that occurred in France after the war, of which Cocteau was forced to defend his ambiguous, apolitical position taken during the occupation.

The original narrative focus of the myth comes back into play when Orphée’s wife, Eurydice, passes on to the underworld and a deal is made to get her back though at a heavy cost. Orphée must not look at her, though this leads to consequences initially more comedic than serious. The rampant switching of emotional attachment between the four main characters may perhaps seem a little odd, but this is a film that quietly abandons narrative rules and expresses its ideals visually rather than explicitly grounded in reality.

Playing around with our perception of death and channelling post-war angst as well revelling in Cocteau’s homosexuality with overtly feminised male characters, Orphée is one of Cocteau’s greatest filmic achievements both thematically and visually, displaying a subtle desire to experiment with the surreal while expressing an outpouring of personal passions and emotion.

Adam Scovell