The Turin Horse – Reviewed

Nietzsche’s life would never be the same following his experience with The Turin Horse. What did Adam Scovell make of it?

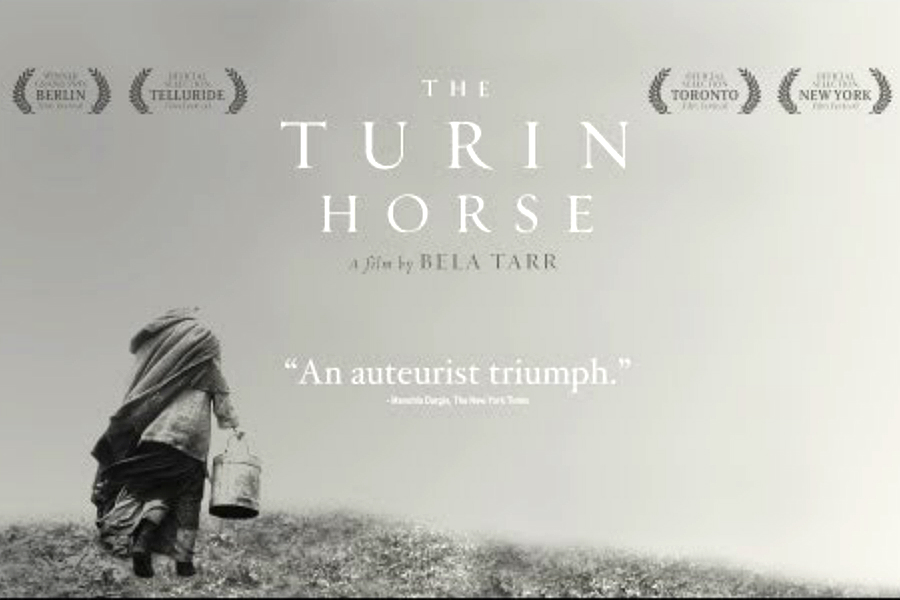

Béla Tarr isn’t a director who likes to make things easy. His films are often bleak evocations of philosophical themes with long running times and deep meditations. The Turin Horse is so much in the vein of a Tarr film that its opening almost verges on self parody. At the same time, it is perhaps one of the most staggering and affecting pieces of cinema Fact have screened of late.

The film revolves around the fallout of philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche’s breakdown following his witnessing of a horse being flogged by its owner. It is at once highly provocative and affirming of Nietzsche’s many philosophical ideas. However, while many directors would have continued along this track, the film doesn’t pursue ‘what happens next’ with Nietzsche. Instead, it explores the tale of the horse and the owner, while at the same time addressing Nietzsche’s ideas.

Following six days in the bleak life of the horse’s owners, an old man who has the use of only one arm and his daughter (who Tarr fans will recognise as the cat-killing girl from Satan’s Tango), the audience are put through the same repetitive struggle that the characters are living through. The shots are extremely long in typical Tarr fashion, with the film being made up of roughly thirty in total. This gives the feel of real time to the narrative and traps the viewer further in the struggling and depressive world of the protagonists. Adding to this is its score by Mihály Vig which repeats and repeats like the days grinding on for the characters. But Groundhog Day, this ain’t.

After being thrust into this world for what seems a lifetime, another character shows up for a drink. Without wishing to give anything away, it is this character who opens up the real crux of the film, as well as showing Tarr’s own philosophy on the subject of the art form. It appears that the world around the characters has been built from the realisation of Nietzsche’s theories surrounding the death of God. This seems to have occurred to the characters too, hope seemingly surrendered to the continually windy world they inhabit.

In fact, the wind in particular is an element of the film that stands out. The soundscapes on Tarr’s films are always interesting and well made: the boots are often heavy, the food squelching, the wind loud and inescapable. Here, it is something employed to greater effect than merely for atmosphere. It seems almost malevolent, stopping the characters from leaving their home and even opening doors. It seems a strange preoccupation of a maker of visual art; something whose presence is only felt through sound and its effect on its surroundings. This sums up Tarr’s filmmaking perfectly though and is why The Turin Horse is a perfect denouement to his career as a director.

More than simply repeating the Nietzschean theory, The Turin Horse mixes in with it a clear loathing for the film industry that comes out as: “They touch, debase, acquire. Touch, debase, acquire!” Tarr has declared this to be his final film and one can’t help think, with the continuing battle between him and the apparent Hollywood takeover of his native Hungary (by a certain creator of multiplex fodder), that he’s also tying in the death of God with the death of cinema as we know it.

The Turin Horse serves perfectly as a much needed shock to the system. It is a black and white, 2D drama with no CGI, no superheroes and very little in the way of musical score. Tarr’s work will be much missed in our digital era, but no one can blame him for his feelings towards the industry. The Turin Horse may be about Nietzsche’s death of God but there’s no doubt that with the tide coming in for film in the wake of the digital revolution, it can be read also, desperately, as a cautionary tale about the death of cinema.

Adam Scovell