The Big Interview: James Newitt

Tasmanian artist James Newitt has been in Liverpool for an Australia Council for the Arts residency. Hannah Pierce wondered how it had informed his practice…

Hosted by Liverpool Biennial in collaboration with The Royal Standard, James is the ninth Australian artist to take up the studio since the residency programme began in 2010.

James’ projects interrogate social and cultural relations by developing ongoing relationships with individuals and communities. Comprising video, sound and text as well as public projects, he creates work through methods of social engagement and documentary observation to investigate spaces between individual and collective identity, memory and history, fact and fiction as well as public and private space.

The Double Negative: Hello James, first things first – what was it that attracted you to a residency in Liverpool?

I first visited Liverpool in 2010 while I was in Europe for some exhibitions. I spent a week here and checked out the Liverpool Biennial ‘Touched’ – the way the Biennial used abandoned buildings allowed for a pretty incredible experience of the city which otherwise probably wouldn’t be possible. I really liked the intensity of the city – it seemed to have a particular attitude while also being quite peripheral and perhaps independent of larger cities like London. At the time I tried to describe the city to friends back home and said it was kind of ‘gritty’ – in a good way. I knew the Australia Council for the Arts had recently begun a studio residency in Liverpool so I thought it was a good opportunity to apply and try and spend more time to get to know Liverpool better, make new work and find out more about the art scene here.

TDN: How have you found it and in what ways does it compare to other residencies that you’ve done previously?

It’s been a really interesting few months, arriving in Liverpool in the dead of winter wasn’t easy but overall I had a great time. I think the most significant difference between this residency and others I’ve been on is the support network, which the Biennial team, and of course the Royal Standard, provided. It makes such a difference to arrive in a new place and be introduced to great social and professional networks – without that residencies can be quite isolating experiences. I think Liverpool’s relatively small size also helps with being able to meet and work with people – it’s not hard to catch up with someone or just bump into them on the street.

TDN: Can you tell us a bit more about the work that you’ve been developing here?

I wanted to use the luxury of having this time and space to play a little more with my work; read, consolidate ideas that needed resolving, etc. I came to Liverpool having recently done a series of works that explore ideas of celebration, conflicting ideologies, and autonomy. I’ve developed these works predominantly through documentary forms and strategies – although I have an uneasy relationship with documentary which stems from questions surrounding notions of ethics, truth, fiction and the role of the artist/author. So anyway, I approached the projects I started in Liverpool through this lens and ended up being drawn to the spectacle of marching bands and protest. There are cross-overs in these two public ‘performances’ but I’m still working on defining them. It’s difficult to speak about work that is still very much in progress.

With the marching bands I specifically looked at the protestant Orange Order and the significance the marching band plays in relation to community, celebration, politics and of course, religion. I made contact with the Star of Toxteth band and recorded a lot of material of them performing, rehearsing as well as interviews. This was a really interesting and quite a confronting process as I was drawn to the intense sense of identity and community which seemed to bind the band together but at the same time I didn’t relate to their underlying religious or political ideologies. Critically I think the of making this work is about issues of relational practice – relationships between the artist and subject – as much as it is about the social and cultural relevance of (protestant) marching bands in the UK.

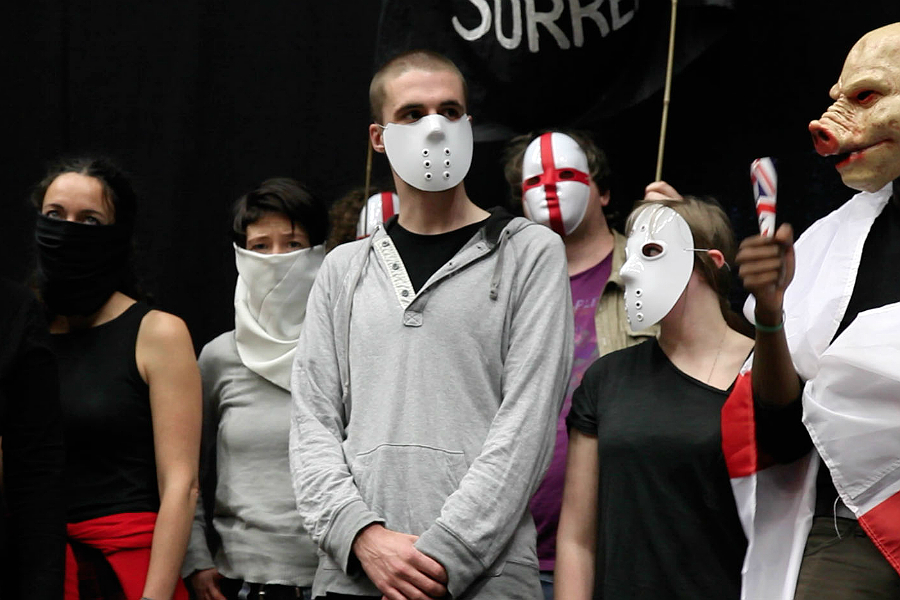

While the work with the protestant marching bands was predominantly observational, I developed another project which was much more performative. This work looked at the idea of ‘staging’ a political protest with a group of people from different contexts who had no previous contact with each other. I wanted to set up a situation where the participants would be asked to shout conflicting political rhetoric with conviction, to do this they would have to temporarily erase their identity and ideologies and shout someone else’s words. With this work I wanted to explore the spaces between hearing something, saying something, understanding something and believing in something – seeing if it is possible to passionately proclaim something you might not personally believe in. I was also interested in creating a situation of high intensity where words might lose meaning and become just sound.

I’ve only just started editing this material so I’m not sure where it will all go exactly.

TDN: Your projects often shift between the observational and the performative, how do you strike the balance between time in front of and behind the camera?

For me, the division between the observational and performative is not so much about being in front or behind the camera. It’s about either observing something from an objective, detached distance or actively creating a situation – fabricating or orchestrating something that is enacted by an individual or a group of people. Of course this division between observational and performative is not clear-cut, I’m very interested in the spaces where observation and performance slip, where it’s unclear if a situation is constructed for the camera or if it’s observed without direction; or whether someone is speaking or behaving candidly or if they are in fact acting, performing. Sometimes I am in front of the camera but I definitely don’t consider myself a performance artist. I always acknowledge my own position within the situations I create or observe – whether it’s behind the camera or in front.

TDN: What’s next for you after the residency?

Trying to find some sun … I’m spending the next couple of months based in Berlin working on the material I shot in Liverpool as well as visiting some of the major events on at the moment like Documenta, Manifesta, Berlin Biennale, and of course the Liverpool Biennial! I’m actually staying in Europe for quite a while as I was lucky enough to be awarded an very generous scholarship from Australia called the Samstag Scholarship which allows me to work as a visiting researcher with a visual art institution of my choice, I’m looking at either working with a school in Dublin or Lisbon for 2013. It feels good to have such an extended time away from home and a great opportunity to try new things.

TDN: What are the three most important things that you’re traveling with?

I feel like I should say my girlfriend but that sounds kind of wrong doesn’t it!?

Close second would have to be my surfboard … I actually spent 3 months looking at it mournfully so I’ll have to find a use for it soon.

Third would be ‘techno bag’, it’s a bag I bought which I use to jam all my camera and computer gear in … I’d be in trouble if I lost that.

TDN: Lastly, do you have any words of advice to artists looking to take on a residency?

I think it’s best to practice what you preach so I’ll give myself some advice in retrospect … don’t stress too much about making new work, procrastinate less, play more (with your work), do more research on the place you’ll work before you leave and maybe leave your surfboard at home.

Hannah Pierce

The next Australian residency artist, Eric Bridgeman, arrives on the 6th June