The Foundations of Metropolis

Nik Glover on the difficult history of a restored masterpiece…

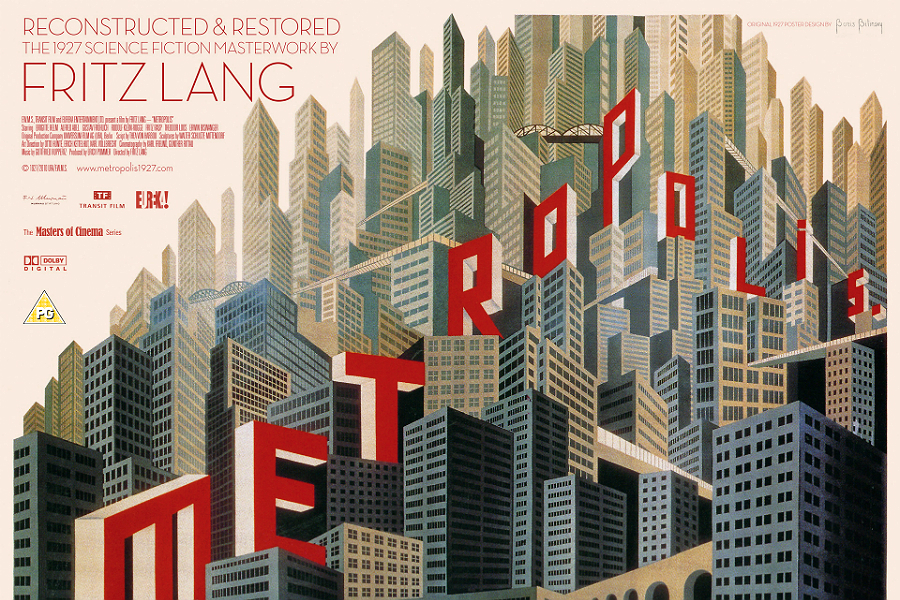

What would your perfect city look like? Before you begin designing your futuristic ‘learning spaces’, hundred story-high art galleries and lush tropical gardens, you’d better think a bit about what sort of people are going to be living there, and who will be working the machines that power the whole thing. For reference, you may wish to attend Picturehouse at Fact’s screening of Fritz Lang’s masterpiece, Metropolis.

Lang’s visionary statement about power, propaganda and class has undergone more transformations, re-edits and re-evaluations than most films worthy of the title masterpieces; excepting perhaps Ridley Scott’s homage, Blade Runner. The cut that premiered in 1927 was believed lost for 80 years, in which time the film was edited and re-edited, with scenes removed, switched around (to ‘simplify’ the narrative) or just plain deleted. Why should such a film, hailed almost immediately on its release as a masterpiece, be shown such scant respect?

Produced between World Wars in the madhouse of Germany’s Weimar Republic, Metropolis was famous, or infamous as Herr Hitler’s favourite film. The totalitarianism of the future state depicted has been read variously as supporting Fascist, Capitalist, and Communist ideologies. Georgio Moroder’s curious 1984 version was colorised and scored by Freddie Mercury, Bonnie Tyler and Pat Benatar. Like tour guides in Jerusalem, editors have turned out cuts glossing over whichever elements they find historically inappropriate or highlight scenes which support their own pro or anti-authoritarian leanings. A film like this, they say, is too unwieldy, too dangerous even, to show uncut.

The years between the World Wars found Germany a melting pot of Nationalist bile, Communist intrigue, thuggish Fascism and wild partying. Hyperinflation caused by the insistence of France and the United States that war reparations must be paid in full (they never were), coupled with civil unrest across the country and the constant rise and fall of national and local governments released amongst the populace an epidemic of creativity. The crowds of workers and aristocrats that flood the streets of Metropolis could be seen everywhere in Weimar Germany.

The war years had seen a ban on the importation of any films perceived as countering the ultra-Nationalist principles of the Kaiser. In the vacuum that followed, and fuelled by an explosion in cinema-going, film-makers began to experiment with Expressionist set and lighting designs which made bold play of light and shadow to cast a Gothic, introspective gloom over their subjects.

Universum Film AG (Ufa), who produced Metropolis as well as the Expressionist masterpieces Nosferatu (1922) and Der Golem (1920), poured money into the grand enterprise of producing cinematic works on an immense scale. Ufa invited journalists onto the set of Metropolis to witness the most spectacular scenes of flooding and mass demonstration for themselves (an act which predates and informs modern viral campaigns). One journalist said of the experience:

“…a glaring flash of light, a terrifying detonation, one of the gigantic escalators breaks down with a terrifying crash. Licking flames, smoke, splinters, destruction… a daring deed that could not be permitted to fail…”

At its German premiere, the Ufa-Palast theatre was transformed into a ‘silver building that gleams like a beacon in the night’, with a reproduction of a giant bell rung during the flooding scene placed in the inner foyer. The production was monumental; the returns were expected to be equally impressive. Yet there was more to Fritz Lang’s vision than the generation of profits for Ufa’s backers.

In 1924, Lang, a young student of architecture, visited Manhattan. The central debate then taking shape in German architecture lay between the varying aspects of communal consciousness suggested on the one hand by the cathedrals of the Gothic tradition (held as monuments to a long-evolving Nationalist Germany) and on the other by the rising American skyscrapers (the very essence of individualism and ‘new money’). Which would the German citizens choose as their future ‘cathedrals’? How would a new German community be shaped: by communion with its past, or in lonely, grasping Capitalism?

The Modernist architecture of Germany in the 20’s makes itself felt in the tenement blocks of the workers’ quarters of Metropolis. In contrast, the imposing Second Tower of Babel represents both the cathedral and the hub of this city-machine. Just as Lang would have witnessed the machinery of the Boss system in New York (which reduced immigrants to voting units even as it fed and clothed them) the new Babel is the power plant, and the seat of authority for the entire city. The singular leader, a technocrat who orders the construction of a robotic spy to weed out dissent in the downtrodden masses, was about as close to the bone as it is possible to get in a Germany being both stripped bare, and created afresh, by the victorious Allies.

A film this reflective of an uncomfortable reality, this in-tune to the madness of 20’s Europe, was bound to make audiences feel uneasy. On its German release, left wing commentators denounced the sight of workers destroying their own homes as Fascist. The Right (including the film’s American editor, Channing Pollock) saw the violent uprising against a dissolute Bourgeoisie as distinctly Communist.

The version eventually released in the US (in the same year as The Jazz Singer rang the death knell of the silent era) had been re-structured so as to remove all reference to the character Hel (considered too much of a risk, sounding the same as the English Hell) and truncating the plot to the point of making it nonsensical. In 2008 the mega-city was restored to its former glory. Prints of Lang’s original cut were discovered concurrently in Argentina and New Zealand, and upon combination produced the version that will be screened at Fact.

Luis Bunuel’s comment that Metropolis was ‘trivial, pretentious, pedantic, hackneyed romanticism… (and) the most marvellous picture book imaginable’ is worthy to illustrate this first and most savage example of ‘total’ film. Like Apocalypse Now, the filming process would subject its stars to horrendous suffering, combining incredible artistic imagination with overblown moralising. Similarly, what resulted was a film attuned perfectly to the age that spawned it; an age of hope, dissent, cruelty and hysteria, and one which would be dreadfully overshadowed by the events of the coming decade.

Nik Glover

FACT screen the restored Metropolis Sunday 22nd April