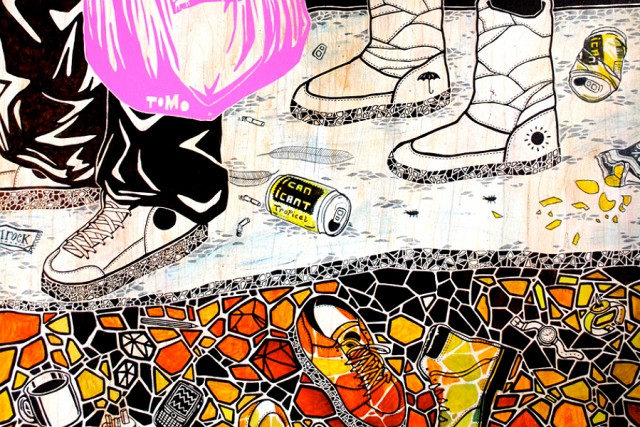

Artist of the Month: Tomo

We put our hoodies on and venture into the unlit streets with our new Artist of the Month, Tomo…

“He’s a mysterious fellow, that Tomo, you know.” This is the reaction we get on telling a surprised friend (and fan) that we’re interviewing street artist Tomo, recently nominated and subsequently shortlisted for the prestigious Liverpool Art Prize (opening tonight).

Influenced by Andy Warhol, Basquiat, and Max Ernst, Tomo’s work depicts people living in the city, working in print and illustration through paste-ups on forgotten walls. You may recognise his work from Lost Properties in February, where he gathered up a team of friends to take over a deserted shopfront on Renshaw Street for a week of pop-up exhibitions, screenings and storytelling. The characters he creates are like you and me: drinking from cans, carrying plastic bags full of shopping, hanging out together. The only difference is, some of these characters will be hybrid animals or vagabonds, with the cracks of urban living peeping through – glimses (literally) into the minds of others or what happens under the pavements that we step on.

We meet the artist, originally from Huyton (nodding to his birthplace with our banner, entitled Huytoned State Of Awareness), in his curiosity-shop style studio at Wolstenholme Creative Space; full to the ceiling with artworks, found signs, knick-knacks, and printing screens. A graphic designer by trade (he graduated from LJMU’s Graphic Arts BA in 2005), his passion for graffiti grew from childhood.

“I’d been into graffiti as a kid. I’d see a nice piece at the side of a motorway when driving with the family, my eyes glued to it! But it wasn’t until my teens that one day, all of a sudden, all of the tags that had normally been invisible bounced out. I was looking at every piece of writing that I could on the wall, memorising where everything was and noticing when pieces were new; even just a little scribble. I met a few people that were doing graffiti, and started tagging up.” Where did you draw your first piece of street art? “I wouldn’t want to say … it’s a secret, but it’s still there!”

A trip to New York only intensified his interest in art on the streets. Blagging a place on a children’s summer camp, working in a stable – “I didn’t know anything about horses” – Tomo seized the opportunity to explore a city full of music-inspired graffiti. “The reason I’d wanted to go to NY was because it was the birthplace of Hip Hop and modern day graffiti. I wasn’t good at graffiti – my can control with spray cans is pretty crap – I’ve always been more of a drawer. But in the early 2000s when street art was getting a lot of attention, I was just getting more and more interested. Seeing the conflict between the two movements – some of the more hardcore graffiti writers proper hating on street artwork – was really interesting to me.”

Not content with just seeing the US style, Tomo developed a taste for street art a little closer to home, leading to some adventures hitchhiking around Europe. “The European styles were much more up my street – I could relate to them more than what I’d seen in America. I didn’t have much money; a fella I’d met in the Egg Café had been a squatter and gave me a few pointers! I did some research and there’s an underground network of socialist centres in Italy, a movement that goes back to the 70s. Basically, I located as many of them as I could, went to Italy and just turned up at the places.” Aged about 21 or 22 years old, in the summer of university, Tomo ended up staying at a historic social centre in Milan called Leon Cavallo, based in what used to be a Fiat factory. “The police tried to evict them in the 70s, but they fought back and got to stay there. It’s just old people, old ladies growing vegetables, all kinds of people; the place is completely plastered in graffiti … I didn’t want to leave. I didn’t speak any Italian. All types of people go there, the whole neighbourhood uses it as a community centre. As part of my keep, they realised I could draw, so I’d just draw things for people all the time and painted some murals for the place.”

Whilst there, Tomo learnt more about the culture of Italian street-art and how it is expressed. “The Italian kids see graffiti as a real source of adrenaline, hitting rooftops and trains; street art is seen as really arty or pretentious, like putting a sticker on a lamppost. There’s a real division.”

Not feeling like experts on street-art culture in Liverpool, we ask: does it have one? “Liverpool has a street style; it’s always been small, but the graffiti scene’s still going. It’s not being passed down as much now, not as much as when I started. I think people have been doing graffiti passing through, travelling up and down the country. There’s new street art popping up; there’s a French lad doing stencils, you can see them in the car park on Slater Street/Seel Street. It’s quite intricate; one of his pieces is called Psyko. Then there’s Sicknote doing paste-ups of creatures and monsters; he’s done a piece at the back of Tabac, which is a recurring spot.”

With so much new building going on in the city, do places still exist for people to get into graffiti art? “There’s always been spots, a lot of them have gone though; maybe that’s one of the reasons why a lot of street artists have gone. There used to be a great spot in China town behind the new college building, there’s a bit of a hot spot in the car park on Duke Street, and the back of Renshaw Street. There used to be a legal wall at Jump Street Rat gallery, which is now Brink bar; that’s where I first met graffiti artists. You could go down on a Saturday and there’d be loads of kids drawing there. Fing is a local legend; he had a really nice style. A lot of the kids really looked up to an artist called Stok.”

Tomo brings up a really interesting discussion about our streets; we talk in depth about the privatisation of Liverpool public spaces, and what it feels like to have control of where you live. “It’s more gentrified around this neighbourhood now so it’s less common to see street art. I almost see it as a struggle against nature; you’ve got all these layers building up, you’ve got wild stuff you can’t control, so let’s gloss it over with something clean and blank.

“I don’t think there’s anything wrong with doing a permission piece, as long as you get to keep your creative integrity – not being told what to paint, like. Sometimes you can paint something much more detailed legally than you normally would be able to do illegally, because there’s less time restriction – you always have to watch out when you’re doing something illegal. I think it has more energy when it’s illegal – it’s not about asking for permission really, it’s really a democracy.”

So do you think that everyone should be into street art? “There should be a space for everyone’s voice. If there’s a space not being used, go out there and take it. It’ll either last and have an effect, or just wither away and be painted over by someone else. Sometimes people ask me for advice on how to do street art and I always say – just do it, that’s the best way to find out! If I put posters up, I don’t much mind doing it on a busy Saturday afternoon. People aren’t that bothered – there’s already enough to look at. I try to keep my head down. I do it because its fun.”

And that’s how Tomo’s work stands out from other street artists. He has a passion for where he lives and how we all live here. He prefers to use the city’s neglected walls and unused materials as his canvas, hating waste, seeing potential in the discarded, but without a loud agenda.

“I work with any materials I can find; if I find a nice bit of wood I’ll bring it back to the studio and start painting on it. I’m more inclined to do that than buy a load of new canvas. It’s about adding my own layer to something that’s already got a bit of history; especially my new work, it’s more about the layers, looking underneath and beyond and seeing what’s there.” His reoccurring characters include drawn bin-bags, petrol cans, owls and running men. “One of my characters is based on the recycling symbol on McDonalds packets, Ronald McDonald running and throwing something in the bin. The owl symbol comes from just being a night-owl; I’m a bit more of a day person nowadays, but years ago I’d just work straight through the night and sleep in the day.”

He makes a quiet statement with his actions that is gaining him a large band of loyal followers, who sometimes take his work down as soon as it appears, pasted up on the streets. His illustrative screenprints and drawings could grace any gallery wall, without being necessarily labelled or recognised as ‘street-art’. So next time you’re out walking in Liverpool, hurrying along, remember to keep a look out for artists who use the streets as their gallery; free art for your viewing pleasure that might have disappeared next time you look.

Join Tomo’s mail art project and receive a beautiful screenprint in return for taking part in secret missions

Images courtesy Tomo and photographer Claire Freeman