Paul Almásy: Making Absence Present

A tale of bravery and foresight in the face of Nazi occupation: Tate Liverpool’s Exhibitions and Displays Curator Darren Pih shares the shocking true story behind a photograph pivotal to their current show…

The first work encountered by visitors on entering the An Imagined Museum exhibition is by Paul Almásy, a Hungarian photojournalist who immigrated to France in 1934. Almásy’s photograph was taken at the Louvre Museum in Paris, articulating the theme of artworks needing to be remembered by documenting an actual historical event. In 1938 with the threat of war looming, the Louvre curators, under the direction of the museum’s deputy head Jacques Jaujard, were compelled to evacuate the entire museum collection, moving it to châteaux deep in the French countryside and away from imminent danger.

In Almásy’s photograph we can see the artist names and inventory numbers for each absent painting inscribed inside the empty frame apertures. Clearly, while the image is suggestive of loss, there was hope too in the form of an expectation that all the works would return and be re-installed in their original locations.

For me, Almásy’s photograph is cautionary, presenting an absence of art. It is making absence present as a concern, and documenting a moment when values and freedoms were under attack. Against the backdrop of the rise of German nationalism through the 1930s, the term ‘degenerate’ was a central tenet of the Nazis’ art policy, used in a propagandist way in their battle against the supposed degeneration of art, usually from foreign influence.

As well as plundering artworks belonging to prominent Jewish families and dealers, almost 16,000 artworks are recorded as being confiscated from German museums alone. The Louvre curators surely understood an attack on art to also constitute an assault on values fundamental to civilisation, the confiscation or destruction of art equating to a form of historical erasure.

Yet against this backdrop, the French scholar André Malraux envisaged a re-definition of the parameters of the museum, not unrelated to the very real possibility of a future without art objects. His 1947 essay Le Musée Imaginaire (translated as the ‘museum without walls’) imagined a museum in book form, its images liberated from historical context as well as museums’ usual systems of classifying works of art, and able to be rearranged in the mind of the reader to create new meanings.

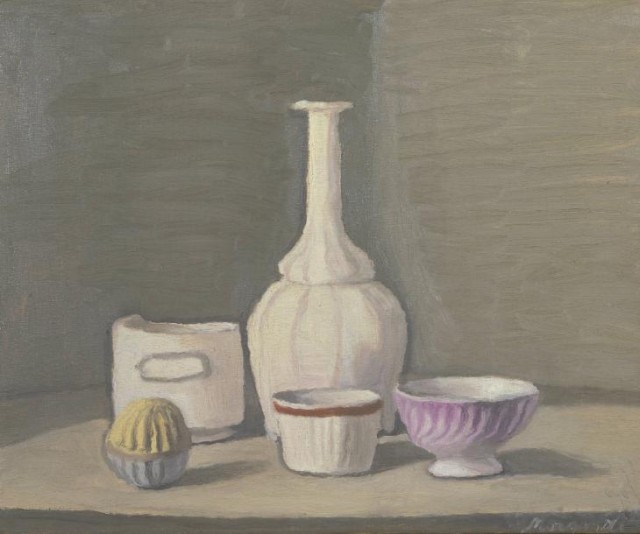

Malraux and the Louvre’s Jaujard et al recognised art’s regenerative role for society, a role that remains a concern to this day. This conviction underpins the selection of artworks in An Imagined Museum, which asks audiences ‘which artworks should we remember for the future?’ Structured according to values which might be considered vital and essential in today’s society, the exhibition brings together major artworks by artists including Giorgio Morandi, whose almost ghost-like still-life paintings (above) convey a personal sense of time and of the reach of memory; Elaine Sturtevant, who asserts the persistence of a mental afterimage while questioning notions of authorship through her ‘replica’ of an Andy Warhol painting created from memory; and Dan Graham, whose video feedback installations play with perception, allowing audiences to actually experience a form of time travel.

The exhibition culminates in a celebratory weekend, during which artworks will be replaced by people. Which works and ideas in art do you think are essential for society? What do you think would happen if we could only rely on image reproductions or memories of artworks?

Darren Pih

This essay is taken from Tate Liverpool’s new seasonal publication Compass. Available for £1, exclusively at Tate Liverpool, it features articles and essays exploring exhibitions on each floor of the gallery. Find out more information about Compass here

See Works to Know by Heart: An Imagined Museum – Works from the Pompidou, Tate and MMK collections — at Tate Liverpool (UK) from Friday 20 November 2015-14 February 2016

The Double Negative presents a special charity screening of Fahrenheit 451 (1966) at A Small Cinema, Liverpool, in collaboration with Tate Liverpool, on Thursday 21 January 2016. Doors 7pm; event starts 7.30-10pm (sold out). All profits go to The Whitechapel Centre: the leading homeless and housing charity for the Liverpool region. More info here

Further reading:

“Art actually is under threat”: What Would You Save In An Imagined Museum?

“Memory’s power to grant meaning”: An Imagined Museum — Reviewed

Images: top: Paul Almasy’s Louvre Paris (1942). Centre: Still Life (1946) by Giorgio Morandi (1890-1964), presented to Tate by Studio d’Arte Palma, Rome 1947