“A form imbued with symbolic potency”: Diagrams

Visiting Holden Gallery’s latest exhibition, Luke Healey analyses the ‘diagram’ through the prism of art, football (!) and pseudoscience…

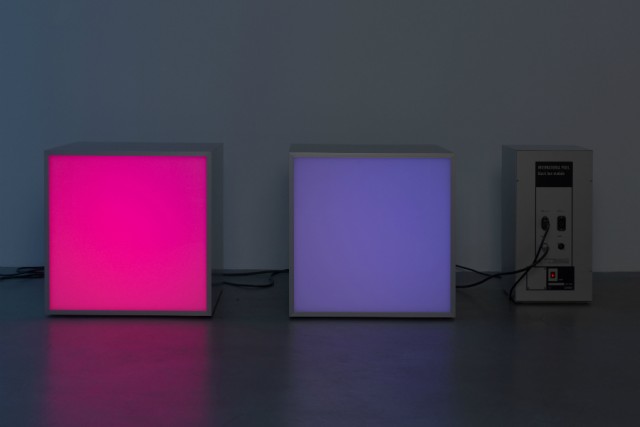

There’s a spartan feel to the current show at Manchester Metropolitan University’s Holden Gallery. Despite the insistent blinking of Angela Bulloch’s multi-coloured light boxes, the most prominent pieces in this display are the rather technical-looking vinyl transfers installed over three walls of the space.

While devising Diagrams, one artist was clearly uppermost in curator Tom Emery’s mind: “It basically comes from the fact that I’m a fan of Simon Patterson.” Emery had worked on this relatively under-represented Young British Artist in a previous venture, and his thinking around Patterson’s practice offers an insight into where diagrammatic drawing — which is unsurprisingly the theme of this exhibition — fits into the discourse of contemporary art.

“I was looking at wider issues around the use of text in art, how text works don’t exist as unique objects, and [how] you can easily recreate the works without the artist’s permission,” Emery states. “They question the idea of originality; why is an original text piece worth so much more than one you’ve just made yourself?”

As a mode of drawing, the diagram eschews traditional artistic values like individual touch and expression — the hallmarks of artistic originality — in favour of values with a more ‘positivist’ (that there is valid knowledge, or truth, only in scientific knowledge) ring, like transferability and legibility. Artistic appropriation of the diagram might be most easily associated with the conceptual turn of the ‘60s and ‘70s, with artists like Sol LeWitt and Mel Bochner, and with the radical process of ‘de-materialisation’ and ‘de-skilling’ which define that chapter in the history of post-war art.

The thing is, the artists involved in this movement never fully submitted to the reductive positivism that their efforts seemed pointed towards: just look at the way colour comes flooding into LeWitt’s later work like a return of the repressed intangible.

Emery’s show does not incorporate works from this earlier generation of diagram-making artists, but it tells a similar story to the one just outlined: for all the ostensible bald positivism of these works, they are full of slippage and uncertainty, full of the deep dark stuff of life. For the curator, “that uncertainty seems to me to be down to the fact that it’s artists that made them – uncertainty is something inherent in art.”

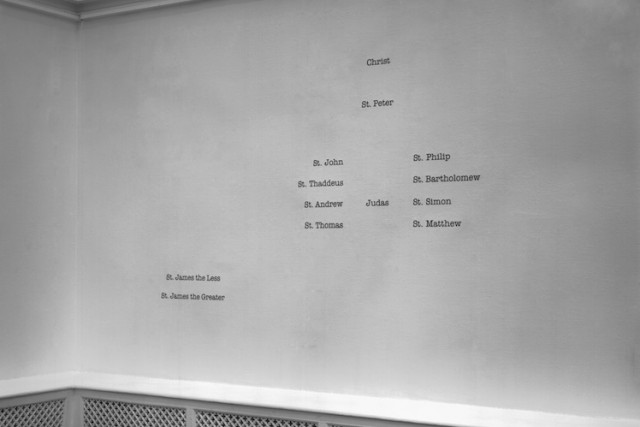

In Patterson’s work, the positivism of the diagram is undone by means of humour; specifically, that bathetic vein of humour that runs throughout the work of other YBA’s like Sarah Lucas and Gavin Turk. The works The Last Supper According to the Flat Back Four Formation (Jesus Christ in Goal) and The Last Supper According to the Sweeper Formation (Jesus Christ in Goal), both created in 1990, carry on a joke which was memorably made a couple of decades earlier, in Monty Python’s sketch The Philosophers’ Football Match. There, Hegel and Kant dispute an offside decision by arguing over the nature of reality; here, St. Bartholomew plays holding midfielder while St. Thaddeus sits in the hole behind the front two.

Football is of course a fertile ground for exploring the relationship between the purity of the diagram and the messier textures of lived experience, given the proclivities of pundits and coaches alike to attempt to reduce real collective effort on the field to a series of dots and arrows. The formation itself, as particularly evinced by those teams at the forefront of the modern tactical game, is an abstraction of the much more fluid course of movements that transpires across the 90 minutes of play.

Emery notes that “football formations have always appealed to me because for a while I was very addicted to playing Football Manager, and playing around and making weird formations is one of the most fun things on that game.” The fun, presumably, has something to do with the slippages and tensions that exist between the pristine algorithm of the ‘flat back four’ and its iteration in the real world — or, at least, the computerised world.

Patterson’s work actually says little about this: the football formation is appropriated more as one of the conflicting terms in a simple one-liner whose effect wears off before long.

More compelling is Mark Titchner’s large-scale drawing Symbolic Hieronymous Machine (Gold) (2014), which, like Patterson’s pieces, is directly transferred onto the gallery wall in vinyl. The visitor to the space is struck immediately by this beautifully-wrought network of lines and curves, which is soon recognisable as a circuit diagram. This is to say, the viewer flips from one mode of viewing to another, as the drawing emerges as something to be read rather than merely contemplated.

Mystery fills up the work once more, however, when we learn what the diagram actually depicts: the titular Hieronymus Machine, a device designed to detect the so-called ‘eloptic radiation’ signature of objects. Emery points out that the device belongs to a branch of pseudo-science known as radionics: “I guess one of the main things that radionics machines try to do is heal people and cure illness; it’s not quite spiritualist, because it’s supposed to be based in science.”

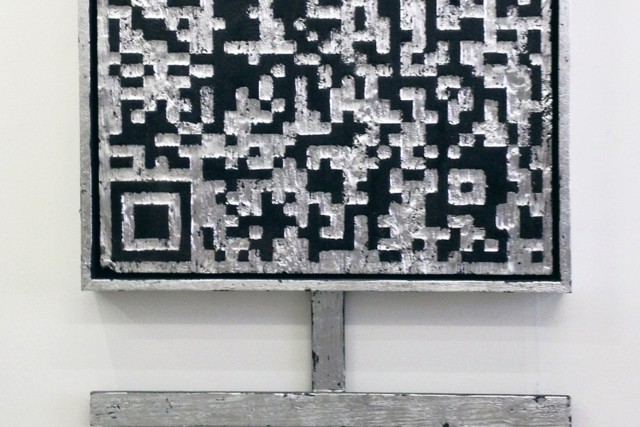

Nevertheless, the device’s function is dubious at best, as eloptic radiation has never been proven to exist. Here then, the rational and the irrational co-inhabit the same visual object, which gives lucid expression to a thoroughly mystical and obscurantist concept. This tension is repeated in the other work by Titchner included here, WHITE STAINS (2012), in which a symbol of everyday technological rationalism, the QR Code, emerges from a burnt wood carving, offering smart phone users the chance to download a pornographic poem by British occultist Aleister Crowley.

Carrying this tension into a more politicised territory are two works by Langlands & Bell: Logo Works is a series of prints reproducing the floor plans of the headquarters of various major companies, including BMW, Unilever and IBM. The way the BMW headquarters is based around the company’s logo reflects a reverential preoccupation with that icon that touches on the mystical.

Rather than favouring expediency, this structure congeals around a form imbued with symbolic potency, connecting it with religious structures of the denigrated pre-modern past. Langlands & Bell hereby align themselves with what has been called gothic-Marxism, with a Marxist critique which seeks in particular to reveal the magical myth-making that Capitalism takes as foundational, in contrast to its emphasis on clear-headed thinking.

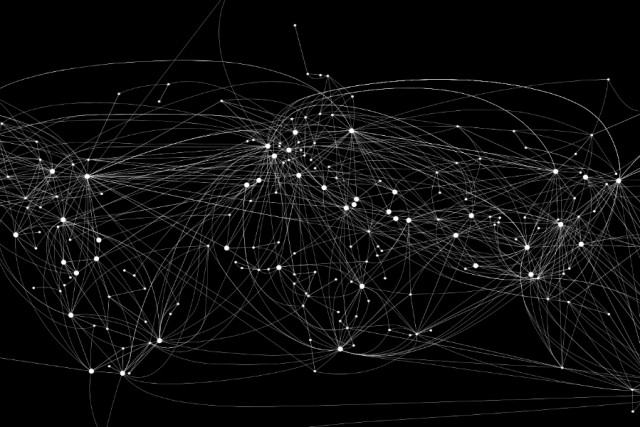

The constellation created by air travel routes in their film Air Routes of the World serves a similar purpose, turning the international circulation on which 21st century capital is reliant into a seductive cosmological image. Here, the diagram is so much more than a mute vessel for abstract truths. Instead, it opts to dance with those forces which diagrammatic logic disavows: beauty, and the wider social framework in which the diagram finds its voice.

While ostensibly growing out of a somewhat underwhelming body of work (Simon Patterson’s), Diagrams ends up giving us a number of compelling reasons to think seriously about this marginalised form of drawing.

Luke Healey

Diagrams runs until 28 February 2014 at The Holden Gallery, MMU — free entry, open 10am-4pm