Field Trip: Art Basel And Manifesta 11, Switzerland

What have great bales of poo, a “pavilion of reflections”, banks of iPhone chargers and glossy sculpture halls got in common? Switzerland during art fair season, finds Jack Welsh…

Admittedly, flying to one of the few non-EU countries in Europe, just a few days before the EU Referendum, wasn’t the greatest omen.

After baggage reclaim at EuroAirport Basel Mulhouse Freiburg, my angst-ridden British soul was greeted by a rather unique exit system. On leaving, you have two options. Either, take the exit to the left: GERMANY / FRANCE, or turn right into: SWITZERLAND.

Occupying a unique geographical position in the heart of Europe, Basel straddles the borders of France and Germany with many residents exploiting the Schengen agreement to freely live and work across different borders.

Despite this, the underlying context of choosing to enter into Europe or non-EU territory wasn’t lost on me.

Basel is an affluent city dominated by chemical and pharmaceutical industries, perhaps best symbolised by the colossal Roche-Tower; a rigid Herzog & de Meuron building housing many of the 10,000 Basel citizens employed by Roche. It stands solemnly on the bank of the swollen Rhine, aggravated by recent heavy rainfall, which, my benevolent Hungarian Airbnb host tells me, is where locals tie inflatable bags around themselves and drift downriver in the searing summer heat.

In late May, Basel was invaded by thousands of Scousers for Liverpool’s ultimately unsuccessful tilt at Europa League final glory. Barely a month later, a more liberal occupation occurred as international curators and artists arrived for one of the major events on the artworld calendar: Art Basel. Like the forthcoming Liverpool Biennial, the Basel cultural scene gravitates around the fair, with every venue pulling out the stops to entice attendees into exploring the city’s wider cultural offer.

I took advantage of the special opening hours for Museum Tinguely early on Saturday morning. Founded to celebrate one of Basel’s most famous sons, the museum houses many of Jean Tinguely’s kinetic sculptural works. Masculine, charming, poetic, sexual, but always unpredictable, Tinguely’s works are joyful. However, there’s an inescapable sadness when witnessing these doomed machines housed within a sterile environment, something the artist himself acknowledged.

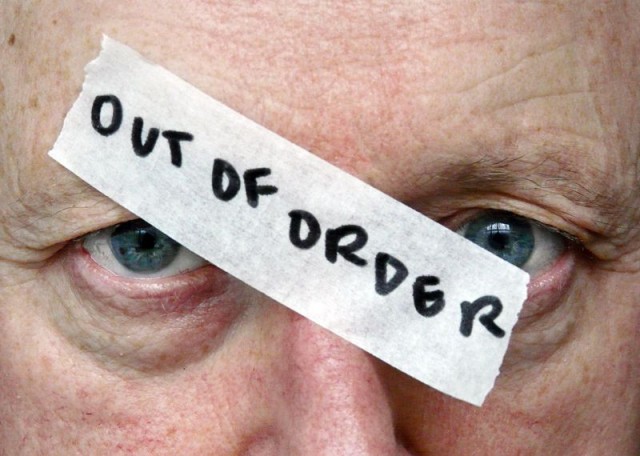

Museum Tinguely has generated considerable buzz due to hosting Out of Order: Michael Landy’s first major museum retrospective. In a delightful start to the day, I had nearly an hour in the show to myself, which, in these times of aggressively jostling for position in heaving institutions, felt like a true luxury.

Out of Order brings together pivotal works by Landy into an immersive and non-linear installation. Artificial grass and plastic bread-crates (Appropriation 3, 1990) giant self-abusing saints (Saints Alive, 2013) and a credit-card-eating machine all mesh together works to vibrant effect. The influence of Tinguely, with whom Landy exhibited with at Tate Liverpool in 2009, is clearly evident.

Yet it’s the arresting red and white drawings from Breaking News (2015) which hit home hardest. Utilising a monumental wall, Landy creates a contemporary mosaic of despair filled with popular culture, market forces and unseemly undercurrents. Words and phrases jump out in no order: Sports Direct. ISIS. Corbyn. Vote Leave. At a time when the concept of Britishness is the subject of severe national introspection, it feels vital that this is being exhibited abroad.

Across town, Art Basel is held at the impressive Messe Basel New Hall; another Herzog & de Meuron designed building, it’s a conference centre with a metallic and expensive façade wrapped around it. It’s fitting, given that bombastic scale and excess are Art Basel’s calling cards.

On the ground floor is Unlimited, an exhibition facilitating large-scale works and installations from top tier artists. Several works stand out. David Balula’s Mimed Sculptures (2016) is one of the first works. Featuring mimes (wearing pristine pink gloves) miming the dimensions of key modernist sculptures, it’s a popular draw, but its contextual smugness diminishes its effectiveness beyond an Instagram post.

Alicja Kwade’s Out of Ousia (2016) (above) is an immensely beautiful sculptural work that engages the viewer through poetic materiality and objecthood. Hans op de Beck’s immersive installation The Collector’s House (2016) presents an ambitiously recreated classical house entirely rendered in concrete grey. Viewers are invited to walk around this mise-en-scène, with fag ends, empty bottles and Starbucks cups punctuating the neutralised grand domestic setting. It feels like Pompeii for the LA set.

Spread across the upper two floors is the main art fair itself. In the traditional art-fair format, international gallerists from across the world set out their stall with several hundred works of differing quality but highly policed, sleek uniform presentation.

The general fair vibe is tired but persistent. While the previews ended two days ago, the majority of gallerists look like they’d enjoy a good lie-down instead, exhausted by networking and pitching. I always tend to be more interested in the slippage between public and commercial spaces in art fairs, or more accurately, the enclosed spaces where deals are made. I always try to peek in the cracks that reveal these secret cavities of capital. I also found great satisfaction in counting charging iPhones on the floor (24, if you ask) and how many gallerists had already cracked open the champagne.

For me, these nuances reveal more about the market than the polished displays.

Despite pre-fair concerns, dealers reported that Art Basel generated considerable sales in the private market. Iwan Wirth, partner at Hauser & Wirth, told Art Net: “All in all, we were on fire in Basel.” This assertion felt correct.

After four and a half hours, and several espressos, my basic directional functions begin to fail so I head off on a long walk across town to Volta Art Fair (above). Housed in the stunning concrete dome of the Markthalle, Volta is a platform for rising talent and emerging galleries with a strong track record over its 10 or years. The atmosphere was more relaxed with discussions with gallerists more engaging. A large majority of works were paintings, which may have been due to stylistic, commercial or logistical constraints, or, perhaps more obvious I’d arrived from the extravagant Art Basel.

I finished the day by taking advantage of the evening opening hours at the recently opened extension of the Kunstmuseum (above). The sheer beauty of the venue enhanced a pretty safe sculpture show; polished marble floors in rooms dedicated to single works left me drooling. Utter filth.

I took the train on wet Sunday morning (a slightly longer journey than Liverpool to Manchester) over to Zurich to see the eleventh edition of the nomadic European biennial, Manifesta.

Curated by artist Christian Jankowski, it asks: What people do for money?, and – more specifically – how do external professions and work relate to contemporary art? Mirroring his own practice, Jankowski has orchestrated encounters between artists and Zurich citizens employed in numerous non-art professions, reflecting Manifesta’s adaptation of the geopolitical, social and historical context of its host city.

The core exhibition is entitled The Historical Exhibition: Sites Under Construction, and spilt across various sites; two key venues, Helmhaus and Löwenbräukunst; several satellite sites peppered across Zurich where artworks are installed, activated, or performed; and finally, screenings of documentaries created by film students at The Pavilion of Reflections (top).

An architectural platform floating on Lake Geneva, the pavilion is a calming wooden structure designed by Studio Tom Emerson and local students. It comes complete with social space, café, cinema screen and auditorium, swimming area and a mischievous water jetty from Maurizio Cattelan’s collaboration with Paralympics athlete Edith Wolf-Hunkeler.

What a joy. Living up to its name, the pavilion succeeds in creating a genuine new social space within the city. Locals (who had paid for entry) seemed to be using it for leisure alongside art tourists and day-trippers. I stayed for over an hour drinking in the magnificent views across Lake Zurich and genuinely relishing a beautiful chance to reflect.

In Helmhaus and the Löwenbräukunst, existing works are presented alongside newly commissioned “joint ventures” that aim to thematically address the relationship between art and varying professions. The biggest selection of works is the gigantic Löwenbräukunst, punctuated by Pablo Helguera’s hilarious artworld cartoons drawn straight onto the walls between floors.

One of the key works is Mike Bouchet’s outstandingly titled The Zurich Load (2016) (above): 80-tonnes of human waste (a day’s worth) from a Zurich treatment facility compressed into solid squares. Recalling Judd and Andre’s minimalist sculptures, as well as Manzoni’s ode to artist shit, the work succeeds in creating a spectacular visual spectacle, if not being entirely convincing with its claims of being a collaborative work with the citizens of Zurich.

Unsurprisingly, it smells fucking awful.

Overall Manifesta succeeds where Jankowski’s collaborative ethos is evident. The transformation of Cabaret Voltaire (below), the legendary home of Dada over 100 years ago, into an anarchic Guildhall where new members must performer is loaded with social and contextual relevance. The inclusion of overly familiar works in the Löwenbräukunst (Michael Smith’s How To Get a Group Show still draws hearty belly laughs) creates a didactic framework which dilutes the impact of these fresh exchanges, undermining the fluidity and spark that characterises Jankowski’s own practice.

Reflecting as I write this summary back in Liverpool, post Brexit, I return to Leigh Ledare’s tripartite video installation at Helmhaus. A real-time screening of a three-day immersive Tavistock group observation set up by the artist, Ledare’s work peeled away at the social, class and ethnic boundaries of Zurich citizens within a carefully orchestrated group dynamic. Accompanying the work was the group reflecting on the process they’d undertaken, analysing and evaluating the experience through work displayed in vitrines.

After the unprecedented social and political split of the Leave and Remain campaigns, and the deep-seated issues Brexit has highlighted in the UK, I can’t help but feel we’re at the bitter beginning of a national group therapy session that could last for years.

Jack Welsh

See Manifesta 11 until 18 September 2016 in Zurich, Switzerland

Jack saw Art Basel 16-19 June 2016 in Basel, Switzerland

Images, from top: The Pavilion of Reflections; Out of Order: Michael Landy’s first major museum retrospective at Museum Tinguely (© the artist); Alicja Kwade’s Out of Ousia at Art Basel 2016; Volta Art Fair; Kunstmuseum; Mike Bouchet’s The Zurich Load at Manifesta 11 (© Camilo Brau); Cabaret Voltaire. All images courtesy Jack Welsh unless otherwise stated