Maps Of A Wretched Past: Patrick Altes

What shapes your sense of belonging? French-Algerian artist Patrick Altes attempts to reconcile his identity with the troubled history of his birthplace, finds Stephen Clarke…

Where we were born defines who we are. We feel that we belong to a particular place and that a place belongs to us.

This legacy is questioned in the work of the artist Patrick Altes. Born in Algeria in 1957, Altes grew up in France and has since travelled extensively. His art combines recollection and revisit in his search for an Algerian identity. The art works, currently on show at the Contemporary Art Space Chester (CASC), attempt to reconcile Altes’ identity in relation to the troubled history of his birthplace. Seven large paintings act as the keynote to the exhibition. These canvases have the appearance of maps, with landmasses and blue seas, introducing us to the land of Altes’ birth.

We use maps to find places. As clearly as a pictured scene a map provides an image of a place. Notable on these graphic overviews are colours and shapes that define particular topographies. Altes’ paintings are composed of the yellows, oranges and browns of a desert landscape; most are dominated by sand with inlets of bright blue piercing the edges of this hot and dry terrain.

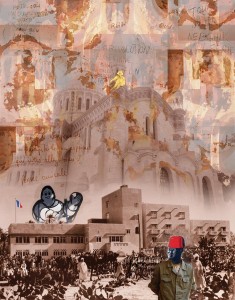

From the bottom of a number of his paintings, such as Gardens of Babylon I (2012), flames seemingly lick towards the top part of the canvas. Heat is connoted by this imagery, which in turn pictures the fires of revolution. In the digital prints that accompany Altes’ paintings, photographs of Algeria past and present, as well as text and drawings, construct a place that lies between memory and experience. In these composites, regional style and colonial architecture come together. In the print Des p’tits Gars bien d’chez nous (2013), a giant Bibendum, the French Michelin man, looks out on to a scene of European rule. The exhibition title, A Story of Revolutions, refers to the violence of the Algerian war of independence; but in Altes’ work the conflict pictured is one of cultures rather than of the blood shed.

Maps are political tools; they define a land and mark out its borders. The continent of Africa, like other parts of the world, was carved up by the European powers; land became colonial possession and its people belonged to a foreign body. The French invaded Algeria in 1830 and the country remained under the administration of France until its independence in 1962. Effectively, North Africans became French and the French came to live in Africa.

Altes’ painting The Civilising Mission (2013) pictures this invasion of a foreign body. At the top of the canvas, a large blood-red creature crawls from the northern land invading the south. Altes’ family were the Europeans that came to live in Algeria, the foreign body that came to stay. Consequently colonialism has tainted Altes’ relationship to his birthplace.

Time is crucial in this relationship, as Altes was born in the midst of the eight-year revolution. The war of independence combined the fight to gain freedom from colonial rule with civil war. Following independence the majority of those who were loyal to France left Algeria. For these ‘Pied-Noirs’ (black foot), the name given to Europeans who lived in North Africa, the colonial past became a mythical place remembered through photographs. It is these photographs that Altes’ digital prints use to question the nostalgia for the past. Some of his prints, such as Classroom Picture (2013), make clear the inequalities of colonial rule.

History forms the content of our maps. Man and nature conspire to shape a place. The names of cities, towns, and streets, along with those of rivers and mountains, label the land. In the text of Altes’ prints, different languages collide in a colonized Babylon. In Tout est calme en Algerie (2013), words obscure the underlying photographic images, whilst at its centre a brown stain spreads across the picture plane like a web or a dried bloodstain. The war of independence was bloody, with both sides resorting to torture and terrorism.

In his book The Wretched of the Earth (1961), the writer Frantz Fanon had stated the need for violence in the fight against oppression. Fanon, a member of the Algerian National Liberation Front, identified violence as the language of the coloniser. It was a language that the colonized would have to use to speak to their oppressor. Blood and text meet in heated exchange.

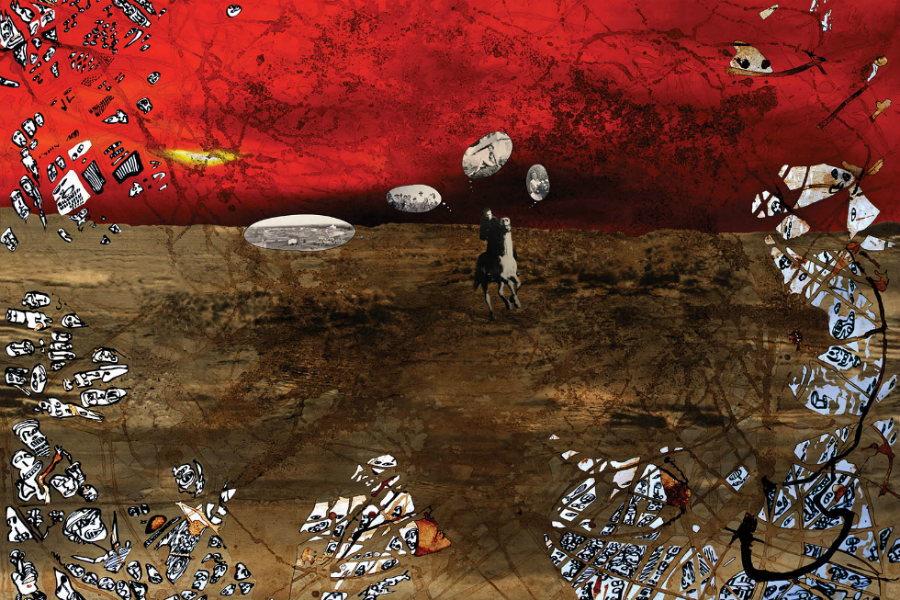

Underneath the surface of Altes’ pictures bubbles the hot lava of memory. The French colonists, displaced following revolution, hold on to their pictures; family snapshot photographs show their Eden, a past existing in the present. In many of Altes’ artworks these old photographs are displayed as thought bubbles poking through to the surface. Critical of this past, Altes challenges the nostalgia of benevolent colonialism to reveal its oppressive nature.

Colonialism has left Altes bereft of a place to belong. In his print Pied Noir Cowboy (2013), a lone figure on horseback travels across a desert scene. No doubt this figure stands in as a self-portrait; the cowboy is a motif of the homeless wanderer moving from place to place; he has few belongings and belongs nowhere. This lack of definition can leave him wretched.

Stephen Clarke is an artist, writer, and lecturer based in the North West

Images: Main: Pied Noir Cowboy (2013); centre: Des p’tits Gars bien d’chez nous (2013). Courtesy Patrick Altes. See more of the artist’s work on his website here

The exhibition Patrick Altes: A Story of Revolutions at Contemporary Art Space Chester (CASC) runs from 9-30 May 2014 and has been curated by Prof. Neil Grant, Head of the department of Art and Design at the University of Chester. Open Mon-Fri 10am-4pm, free entry

A number of the works exhibited at CASC will be part of the 33rd Mediterranean Biennale of Contemporary Arts in Oran (Algeria), 8-10 June 2014