Northern Art Prize 2013

– The Lowdown

C James Fagan heads North to a city with a burgeoning art scene, one playing host to the Northern Arts Prize…

Not for the first time in my life I find myself on the train heading further north, passing through landscape that switches from urban, to post-industrial like a living demonstration of the industrial history of the north. Up through some dramatic snow-topped hills, the kind of which might just win you a slot on the Countryfile calendar.

I’m crossing the Pennines, primarily for the Northern Art Prize, currently awaiting me in the Leeds Art Gallery. On the journey I reflect on our cousin to the East; has this separation allowed Leeds to build its own cultural identity? In the past I’ve associated the city with music, as many bands seem to head there, eschewing the likes of Liverpool. But recently I’ve begun to see an art scene which appears to at once acknowledge and celebrate its past while using that to create an umbrella to show contemporary art.

Leeds now seems to harbour growing ambitions to be a centre of that world; with the opening of the nearby Hepworth Wakefield, the giving over of the city to the Quay Brothers as part of the Cultural Olympiad, and the upcoming opening of The Tetley. It seems natural that Leeds would be home to a prize which will celebrate the best artists based in the north.

Arriving at the Leeds Art Gallery, the first thing I see are two large cartoonish arches sat at the far end of the atrium, giggling and laughing at themselves, like madmen sharing an abstract and invisible joke. Deciding the punchline can wait, I go into the room containing work by Emily Speed and Rosalind Nashashibi. It’s a deliberate decision: in a few moments Emily Speed’s performance will start, giving me a few moments to get to grips with the topography of the space. To the side of me are two constructions which seemed made both haphazardly and with purpose. In front of me there is a bare tree, with an image of a crotch, large cartoon hands on the wall and a number of prints of jeans.

Before I can to begin to breakdown what these disparate items mean there’s a loud metallic bang from behind me, the brakes are off for the performance Carapaces. Two women (adorned in tabards decorated with architectural patterns) enter into a long-legged sculpture and wheel the elephantine vehicle through the gallery which glides around the space, motivations unknown. This hybrid of human and building is a creature born of Speed’s concerns about private and personal space, of mental and physical architecture.

There’s a quote from Freud about how you feel (safe or scared) in which a forest depends on whether you live inside or outside of it, but it’s hard to recall as this multi-limbed generator of personal space comes closer, crashing against your little mental fortress with unknown intent.

I let Carapaces run its graceful path of interruption, and watch Nashashibi’s film Lovely Young People, Beautiful Supple Bodies, quickly making connections between the film and what’s happening outside. Both the film and performance share ideas around the nature of public and private. Nashashibi’s film features members of the public invited to walk through a dance studio and observe ballet dancers as they practice. The public’s comments can be heard along with those of the dancers. At one point a dancer, breathless, repeats apologies to his partner, there is an ambiguity to whose space this is, and through that an exploration into the relationship between performer and audience begins. The third player in this piece is the studio space itself, acting as an enabler, creating an almost hermetic world in which exterior notions of public and private are corrupted.

I can see an element of this in the piece Monster Walk where Nashashibi has created a number of prints using jeans, along with their underwear which makes them look like crude X-Rays. They hang there anonymously and that’s part of the problem. I feel that with some form of knowledge of the wearers’ I might have a sense of looking into someone’s privacy. I feel I’m not getting the whole picture somehow, the same goes for her other piece A New Youth.

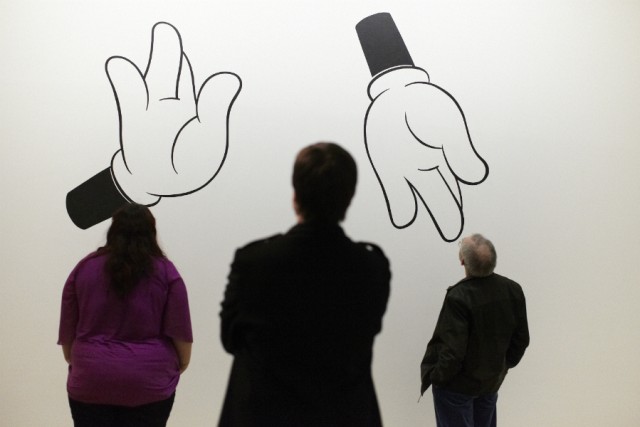

A New Youth comprises a bare tree, Mickey Mouse hands painted on the wall and a black and white photo of a crotch attached to the tree like a poster for a missing pet. I read the information on the wall which has references to Buddha and the reduction of the human condition. Perhaps it’s been reduced too far as these conceptual underpinnings seem gossamer thin as I try to assemble the parts into a cohesive whole. It doesn’t share the deceptive simplicity of the film and feels somehow overworked, overthought in comparison.

On to the psychedelic arches I saw when I first entered the gallery. Created by Joanne Tatham & Tom O’Sullivan these portals generate a sense of childlike excitement – as I draw nearer I become more intrigued by the cartoony wonderland they appear to offer up. Are these portals to another world? If so, what awaits me behind them; will I meet Finn and Jake in the land of Ooo?

Passing through The Reiterative Grimace, this sense of joyous promise evaporates, and I’m in a room of black and white photographs of other sculptures in other rooms. Is this a comment on the fallacy of dreams, a reminder of not judging books by their covers? The information on the wall speaks of the image and its narrative and imaginative possibilities. I definitely had that sense on approaching the arches but once through them that narrative possibility was shut down. Whether this is the intent it’s unclear.

Of course, the narrative of the exhibition is continuing, and a large room with a collection of different objects awaits. Mainly mirrors, reflecting surfaces of different sizes, including a bunch of wing mirrors gathered on the wall, with two large mirrors in the central space, one set behind a grim looking fence covered with personal detritus: photos, clothes, plastic toys. Avoiding my reflection (no need to see that!), I find myself heading to the information board to come to terms what I’m seeing.

Common Reflections is a facsimile of the fence surrounding the American Air Force base of Greenham Common, where a force of women stood up to the Regan Military determined to make the UK into a launch pad for its nuclear weapons. At one point using mirrors to distract the base’s personnel – a great idea which must have been something to see. The imagined image I have of all those women reflecting light off mirrors creating thousands of little novas to distract the grey/green mass of the military machine is stronger than the image presented by Margaret Harrison.

Maybe there’s something in the installation of the piece which makes it difficult to truly get a sense of the collective effort of the women of Greenham Common. There also seems to be installation issues with her other piece, The Last Gaze, which at its core features a painting of a painting based on Tenninson’s poem The Lady of Shallot. They are all reflections of a woman who can only see the world using mirrors, explaining the presence of the wing mirrors. As viewers, we are to view the painting via these mirrors and get a shattered, fragmented image of the painting. The thing is I can see the painting whole on the wall over there, and being able to see it as a whole negates having to look into a mirror. It feels like this piece has been robbed of its power.

With this last room, I’ve reached the end of the shortlist. How do I feel about the Northern Art Prize as an entity? Conflicted. Obviously it’s generated enough interest for me to get on a train and travel all the way to Leeds to see it. There is something very subjective within prizes like these – indeed, any selection process – and the work here constitutes the choices of the judging panel.

So I leave the Northern Art Prize not entirely satisfied, yet not dissatisfied: it’s an odd state. I consider that the NAP is still relatively new (running since 2007), so there’s still that sense of a character being formed and I’ll be back next year to see how the prize and the city have changed.

C James Fagan

The Northern Art Prize exhibition continues at Leeds Art Gallery until June 16th