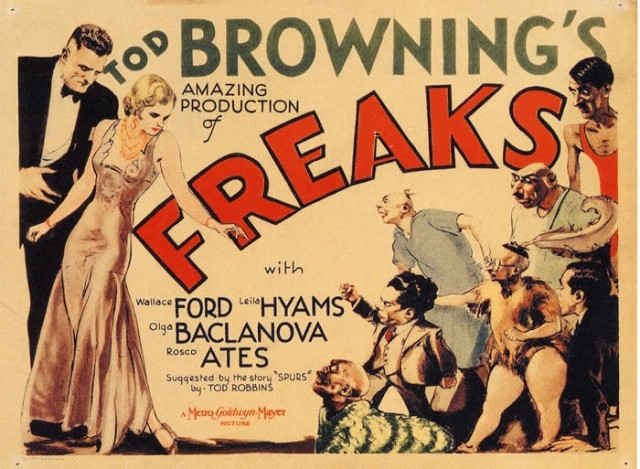

In Profile: Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932)

An ancient curio of subversive Hollywood, or just plain provocative? Adam Scovell analyses what is possibly early cinema’s most uncomfortable horror…

That strange period between American cinema that experimented with early sound, right through to the establishment of the Hollywood Golden Age, is often hugely misrepresented. Usually falsely characterised by the technical problems that the oncoming of sound technology had on the visualisation of cinema and narrative, it’s often forgotten how thematically groundbreaking the early non-slient cinema of America actually was.

In 1935, this rich vein of daring, provocative cinema would be replaced by a safer, more broad form, thanks to the introduction of the Hays Code censorship; but it could not hide the first five years of gritty, nihilistic cinema that Hollywood produced between 1930 and 1935. This was the era that all but defined American horror cinema.

Thanks largely to Universal Studios and their string of successful monster pictures, horror bloomed in pre-code American cinema. Yet, whilst the imagery of these films are now part of the very basic lexicon of horror cinema, it’s easy to forget just how nasty early sound horrors could be. Directors like Tod Browning, James Whale and Erle C. Kenton began to push against the grain, since sound had opened up cinema to new, more troubling topics such as open, frank discussions of sex and violence. Films such as Frankenstein (1931), The Murders In The Rue Morgue (1932) and Dracula (1931) went back to the themes and literature of the Gothic movement of the last century to imbue their films with a sense of the macabre.

Yet, surprisingly, out of all these different films and separate strains of horror, the theme of physical impairment seems to almost be a constant, and nowhere does the theme appear more viscerally than in Tod Browning’s 1932 film, Freaks. In pre-code cinema, no topic is left alone and the questions surrounding disability are a prominent constant in American horror cinema. Of course, this can be traced to earlier silent cinema. Take, for example, the original Hunchback Of Notre Dame (1923) which enlists horror’s first star, Lon Chaney, to take on the role, or even later silent horrors such as The Man Who Laughs (1928) and The Hands of Orlac (1924); two films starring Conrad Veidt as a man troubled horrifically in various ways through physical affliction (the former where his face has been surgically disfigured to be always smiling, the latter where his hands are transplanted with those of a serial killer’s).

These films are startlingly effective but have nowhere near the provocation of Browning’s Freaks. After the success of his adaptation of Dracula in 1931, Browning had free reign for his next film. Whilst he had already been in production for his boxing drama, Iron Man, the success of his first sound horror film had spurred him on to explore the genre further (he had, after all, made the now lost horror film London After Midnight three years before). Freaks is the product of this complete free reign, making a film that is both horrific (for its content and its stylistic portrayal) and deeply personal for the director as well.

The film follows the drama of a group of travelling circus and side-show performers. The circus’ trapeze artist, Cleopatra (Olga Baclanova), is planning on marrying the circus’ midget leader, Hans (Harry Earles). However, her secret is that she is only marrying him for his money — his circus being a huge success — and the drama unfolds as the other performers find out that Hans is being used, eventually exacting a ghastly revenge on the trapeze artist.

Though at first Freaks seems to be exploitative (its title alone is deeply uncomfortable), it arguably shows an oppositional point of view in not to judge by physical appearance. In spite of being marketed as a horror film and also directed in some scenes as if the performers of disability are in the same vein as Karloff or Lugosi, the real heart of Freaks goes against this by showing the evil to actually be in the clichéd non-disabled characters. The villains of the piece are almost Aryan in their physicality and blonde hair, and Baclanova in particular fits comfortably in this bill; the conservative ideas of her beauty bearing horrific sociological fruit. Baclanova herself was a Russian ballet dancer who Browning had used before in The Man Who Laughs, though her role is far more secondary in that film.

Freaks was by no means the only movie in pre-code America to deal with such areas. Island Of Lost Souls (1932), White Zombie (1932) and The Black Cat (1934) are all about the modification of people against their will, whilst The Old Dark House (1932), The Bride of Frankenstein (1935) and Mad Love (a remake of The Hands of Orlac) all feature a character burdened with some form of disability. Freaks stands apart from films dealing with similar issues by using the ‘real’; the film does not simply rely on performance and make-up, but on genuine ailment, which accounts for its powerful affect even by today’s horror standards. The horror is in both the execution and in the treatment of the subject matter itself.

Even in the heady heights of pre-code Hollywood, Freaks simply pushed too many buttons. It was cut by almost half an hour so that it could be deemed suitable for a New York audience, it flopped hugely at the box office all but destroying Browning’s career, and was eventually banned, not to be seen in full again in the UK until 1963 when it was passed with an ‘X’ rating. Even now, its ban is still yet to be repealed in some American states, though it’s doubtful whether it is properly enforced. The reality of using genuine performers with physical impairments pushed it far beyond the acceptability of such a territory; but now, Freaks can be seen as an ancient curio of subversive Hollywood when even the most of extreme ideas were courted with flare and a genuine passion for topics outside of the safe areas of typical narrative drama.

Adam Scovell

Freaks (1932) screens at Liverpool’s A Small Cinema, followed by a post-screening discussion hosted by organiser (and Video Nasties Podcaster) Christopher Brown, on Thursday 30 April 2015, 7.30pm. Running time: 75 minutes

Buy tickets (£5/ CONCS £4) here