“Decidedly Alien”: The Paintings Of Mimei Thompson

Animal, vegetable or mineral? Wayne Burrows finds himself entranced by the luminous, hallucinatory paintings of Mimei Thompson…

Occupying a whole large wall in the final room of Mimei Thompson’s current solo exhibition at Trade Gallery is a small canvas featuring the head and shoulders of a gorilla. Perhaps representing the idea of a gorilla more than any particular member of its species, Ape (2013) is also a liquorice-coloured entanglement of brushstrokes that seems to blend into its own shadow against a vibrant turquoise ground. The ape’s self-possessed, inward-turned gaze — as though, someone said at the opening, it’s experiencing a vision of some kind — seems as much like a hallucination conjured from Thompson’s gestural paint marks as an image of a gorilla.

On one level, of course, this dichotomy between the image and the marks used to imply its presence are at the root of what all painting does: usually glossed or exploited for expressive ends, it’s in the very nature of the medium that paint creates an illusion of some kind, constructing space or seeming to have become flesh, stone or foliage. Yet it’s this fundamental dichotomy that is repeatedly and particularly emphasised in Mimei Thompson’s work, where images seem to hover on the edge of emergence among exaggeratedly visible brushstrokes, like temporarily frozen apparitions.

“The paintings go through a liquid stage, where the whole surface is covered in a fluid mix of paint and Liquin medium on a smooth, non-absorbent surface, and that gets moved around and worked into while it’s all still liquid,” Thompson explains of her working method.

“The whole thing might be wiped or brushed off a few times before it settles down. I then go back into this, when it’s dry, and add detail, shadows and highlights, or sometimes make larger changes, over the weeks that follow. It’s really a combination of planning and leaving space for chance and improvisation. I find control and looseness, and other opposites, really useful to work with.”

Looking At Nature, Becoming Vegetable (2013), a seemingly abstract swirl of dark green brushstrokes from which a folkloric Green Man’s head, butterflies and tiny figures have been teased out, might be the clearest example of this process, but other plant-form paintings, like Weeds (2013), Corner Of The Building (2014) and Bonsai Forest (2014), seem to hover equally productively between chance formation and naturalistic observation — between those opposites of ‘looseness and control’ — as the paintwork echoes the unruly formal properties of its subjects. Viewing her strangely translucent Weeds can feel like looking at Albrecht Durer’s renaissance study of grass and wild plants, The Great Piece of Turf (1503), under the influence of psilocybin mushrooms.

That’s not the primary chemical influence cited by Thompson herself, who instead draws attention to the influence of photography — the medium she first studied in Glasgow, before switching to painting around the turn of the millennium.

“There are definitely connections with the magic and pleasure of making images in a darkroom, the trace of reality getting slowly revealed in a chemical tray,” she says of these recent paintings. “It’s there in the way I think about making work. The translucency of the paint creates a luminosity where the whiteness of the surface can glow through. This connects, for me, to the experience of making photographs using light, from negative film, and also to viewing images on screens.”

It’s certainly the case that much of the estranging effect in these paintings comes from that working process in which oil paint is mixed with alkyd resin medium to both preserve the brushstrokes and suspend them on Thompson’s characteristic luminous white, pale grey-green or lilac-pink grounds. The suggestion is often that this gestural brushwork is not deployed to impose an image, but is the visible trace of a mediumistic process: a kind of ectoplasmic turbulence from which resolved images might have emerged by chance.

Thompson has described her painting in performative terms, noting an interest “in the kind of mark making that is the trace of an event, that has something automatic to it – I want the brush marks to remain really dominant.”

It’s the visibility of the brushwork that seems to invest even Thompson’s most mundane and everyday images with their decidedly alien, hallucinatory presence. Among the many everyday things featured on these mostly small-scale canvases are a heap of sprouting potatoes, a split bin-bag, a row of carefully-spaced asparagus stalks, several clusters of weeds, a cartoonishly anthropomorphic cactus, a pair of sad and happy tomatoes, and a series of small paintings of living and dead flies. The images are typically isolated on a smoothly muted ground, instantly recognisable even as they radiate very strange energies.

Binbag Closeup (2014), a painting that hangs in the first room, is a good example. Its figurative qualities emphasise the shiny black paintwork of its split polythene bulk and the vibrant technicolour outpour of the food scraps spilling from it, but it vacillates, as an image, between this straightforward slice of kitchen-corner realism and a monstrous presence: a blindly vomiting Pac Man or ninja variation on a Medieval Gargoyle theme. Binbag Closeup shares the room, wittily enough, with Green Fly and Dead Fly (both 2014), the two small fly paintings suggestively hovering around the bin liner, much as their live counterparts would.

Elsewhere, Potato Sprouts (2014) is conjured from rich, dung-coloured swirls of brown paint and the pale pinkish green forms of new shoots, extruding from the potato skins like tentacles.

These perceptual uncertainties and double-takes seem to relate strongly to certain Surrealist ideas about estrangement and automatism, a connection we might have been particularly encouraged to notice by Thompson’s naming of a previous solo exhibition after a 1935 Max Ernst sculpture, Lunar Asparagus – a connection that also adds an otherworldly nuance to her own 2014 painting, Asparagus (Horizontal).

As Thompson herself explains, her particular interest in Max Ernst’s paintings, notably the ‘dark jungle’ and ‘petrified forest’ works of the 1930s and ’40s, lies in “the feeling they have where things could be animal, vegetable, or mineral. These are ideas that filter into my work naturally, though. It’s not something I deliberately use, in the sense that I’m quoting any particular references. I think I’m more interested in Surrealist ideas than particular works.”

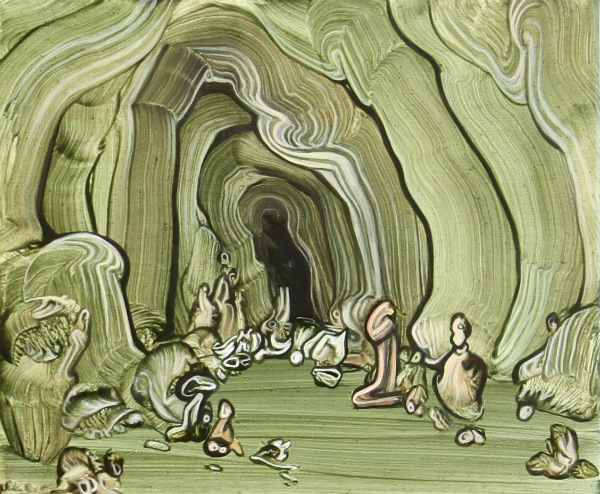

The connection with Surrealist ideas is clearly visible in a pair of small Untitled cave interiors, dating from 2013, where the organic forms of receding underground caverns are lined with strange, hard-to-define forms, as though marking a path into the body and the earth simultaneously with objects that might themselves be rock formations, fleshy organs or plants. As in Eva Švankmajerová’s Baradla Cave, a fiction published in samizdat form in Czechoslovakia during the 1980s, there’s a deliberate merging of bodily and geological presences. The heroine of Švankmajerová’s blackly comic feminist satire, after all, is both a particular woman and the underground cave in which much of the book’s action unfolds: sometimes one, sometimes the other, and occasionally both at once, much as Ernst’s ‘petrified forests’ appear to be formed from indistinguishable rock, vegetation and flesh.

“I am generally interested in the unconscious mind, dream imagery and symbols, the way the everyday becomes fantastic”, Thompson says. “The caves, for me, are about going into a place, with the possibility of coming out changed, or about the unconscious mind.” Yet these archetypal elements are always grounded in that distinctive technique.

“In my thinking, the paintings connect to the idea of insects transforming themselves inside a cocoon. A caterpillar goes through a liquid stage, making a cocoon around itself and then secreting juices, almost digesting itself, and there is a stage where the insect is actually liquid, before it becomes something else. I think there is some analogy there with paint.”

Wayne Burrows

See Mimei Thompson at Trade Gallery, Nottingham, until 11 October 2014, free entry. Gallery open Thursday to Saturday 12-6pm; Monday to Wednesday by appointment

All images courtesy Mimei Thompson and Trade Gallery. More on Mimei here